But "A Midwife's Tale" is a true exception, for it is an exceptional movie. Or should I say it's an exceptional documentary? Hmmm...okay---docu-drama...

Well, whatever you want to call it, it plays so much like a movie that - I swear! - I can't tell the difference.

And this film is very accurate and absolutely can educate...

And it's definitely not of the low caliber quality one sees on The History Channel.

As noted on my DVD case:

As noted on my DVD case:

“In 1784, America was a rough and

chaotic young nation. That year, at the age of 50, Martha Ballard began the

diary that she would keep for the next 27 years, until her death. At a time

when fewer than half the women in America were literate, Ballard faithfully

recorded the weather, her daily household tasks, her midwifery duties (she

delivered close to a thousand babies), her medical practice, and countless

incidents that reveal the turmoil of a new nation -- dizzying social change, intense religious conflict, economic boom and bust -- as well as the grim

realities of disease, domestic violence, and debtor's prison.

In "A Midwife's Tale" the daily activities, the physical feel of the people and buildings involved, and the historical verity that helps us envision late 18th century life, are always conscious - these eighteenth-century details are overlooked treasures that are rich in the texture of everyday life.

Since my initial viewing, A Midwife's Tale has haunted me. No, not in a scary way, but, rather, in such a manner that wills me to now look at historic 18th century houses with more discerning eyes and a more intimate mindset. I will see beyond the walls and presenters to feel the ghosts of those who lived within the walls during the time of the good old colony days.

Ahhh...if only walls could talk indeed!

And yet, they do.

Is A Midwife's Tale a happy and upbeat film?

No.

Oh, there are happy times, but the movie is rather dark and daring.

Real.

In "A Midwife's Tale" the daily activities, the physical feel of the people and buildings involved, and the historical verity that helps us envision late 18th century life, are always conscious - these eighteenth-century details are overlooked treasures that are rich in the texture of everyday life.

The actors in this drama are

unfamiliar. They look like real people, not movie stars. Family dynamics were

more believable and souring relationships took on terrific poignancy.

Martha Ballard is played by actress

Kaiulani Sewall Lee, a direct descendant of the Sewall family of Maine --

people the real Martha Ballard knew, aided in childbirth, and nursed through

illness.”

The story of A Midwife's Tale - the true story - is a wonderful primary source for historians, for this daily diary was put into book-form as a sort of

dissertation/novel by author Laurel Thatcher Ulrich. The

book is a model of social history at its best. Giving portions of Ballard's diary, it recounts the life and times of this obscure Maine housewife and midwife. Using passages from the diary as a starting point for each chapter division, Ulrich, a professor at the University of New Hampshire, demonstrates how the

seemingly trivial details of Ballard's daily life reflect and relate to

prominent themes in the history of the early republic: the role of women in the

economic life of the community, the nature of marriage and sexual relations, the scope of medical knowledge and practice.

From the very beginning, Lahn-Leavitt had the idea of interweaving the story of Martha Ballard's life with author Laurel Ulrich's process of piecing it together. She had planned right from the start to have it begin as a documentary and evolve into a historically accurate drama.

And she succeeded.

With all my years of studying the period, I have never seen any film get it right quite like A Midwife's Tale does. The only other movies I've seen come this close to historic accuracy in sight and sound have been the John Adams HBO mini-series and "Lincoln" starring Daniel Day-Lewis from a few years ago.

Okay...now did I grab your attention?

|

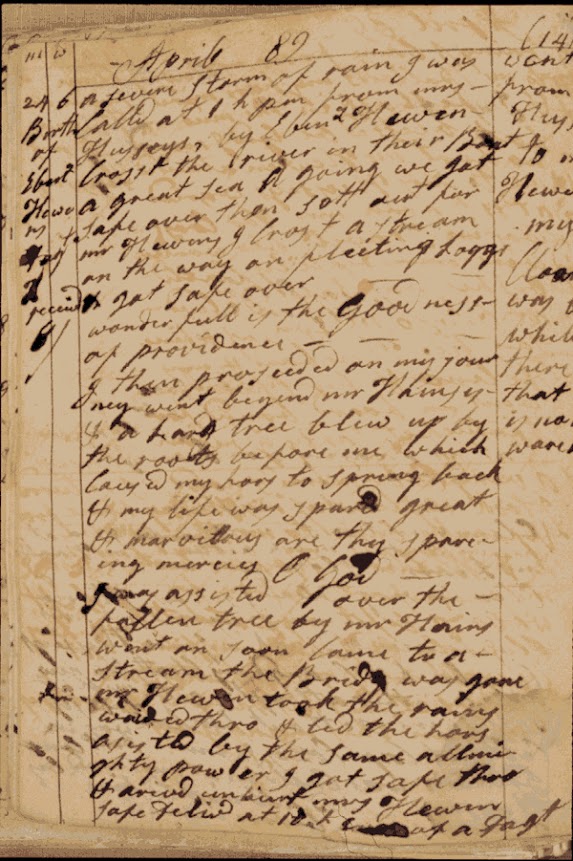

| An original page from Martha Ballard’s diary from 1784 |

Shortly after A

Midwife's Tale was published, Laurie Kahn-Leavitt, a film producer, read a

review of the book, bought a copy, loved it, and worked to secure the film

rights.

From the very beginning, Lahn-Leavitt had the idea of interweaving the story of Martha Ballard's life with author Laurel Ulrich's process of piecing it together. She had planned right from the start to have it begin as a documentary and evolve into a historically accurate drama.

And she succeeded.

Since my initial viewing, A Midwife's Tale has haunted me. No, not in a scary way, but, rather, in such a manner that wills me to now look at historic 18th century houses with more discerning eyes and a more intimate mindset. I will see beyond the walls and presenters to feel the ghosts of those who lived within the walls during the time of the good old colony days.

Ahhh...if only walls could talk indeed!

And yet, they do.

No.

Oh, there are happy times, but the movie is rather dark and daring.

Real.

So real, in fact, that it may seem drab to those who enjoy TV history, for this is a very real peek into an 18th century woman's life with her family and neighbors. No spies. No politics or chases.

Just real life as it was.

So, what I'd like to do here is to show the extent the crew and actors went to in order to create such an accurate window into the past of late 18th century life.

To make that period in history, as I said, real.

So, what I'd like to do here is to show the extent the crew and actors went to in order to create such an accurate window into the past of late 18th century life.

To make that period in history, as I said, real.

The words you are about to read were taken from a web site, DoHistory, which did a case study on piecing together the past from fragments that have survived. The site welcomes historians to share what they have written. This is what I am doing, with only slight modifications.

I hope you enjoy it. And if you do, I hope it entices you to purchase "A Midwife's Tale" in both book and film form.

You will not be sorry.

>>> The past is a foreign place, and a film's portrayal of the past

depends upon thousands of choices about the physical, behavioral, and cultural

details of the period and place being presented. Being authentic or truthful

about the past involves much more than getting the costumes and the

architectural details right.

The extras in A Midwife's Tale were carefully chosen. The production crew hired a calligrapher to double for Kaiulani for the

close-ups of Martha Ballard writing in her diary. They were also determined to

cast real newborns (not six or eight month old babies!) as newborns. The woman

in charge of casting extras called every obstetrician, midwife, and very

pregnant women within a hundred mile radius and used her considerable charm (and some help from an experienced midwife) to convince these parents to let

their newborns be part of the film. They hired local Fredericton townspeople as

Martha's Hallowell neighbors (hundreds of people showed up for the open

auditions advertised in the local newspaper). And there were quite a few sheep, turkeys, horses, oxen, and chickens, too.

As noted earlier in this post, even before the film was thought of, A Midwife's Tale was a book written by Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, and it showed scholars and general readers alike new ways of imagining the past. Speculating on why Ballard kept

the diary as well as why her family saved it, Ulrich highlights the document's

usefulness for historians. “Showing” rather than “telling” is a key distinction here, because the

transformative power of this book is not reducible to a pithy set of scholarly

key words.

~“Clear and spring like. Grew cold at Evening. Snowd some. I have been at home. Irond my cloaths &c.” - Martha Ballard~

Laurel managed to extricate a stunning vision of one woman’s life from such cryptic passages and show us that viewing the world through the writings of one woman in a remote corner of the globe could spur fundamental reassessment of long-established narratives. Laurel saw in this (large) but not especially inspiring cloth-bound diary a promising resource that other historians had failed to appreciate fully. It also demonstrated that economic, medical, legal, religious, and demographic histories need to understand the experiences of women (and of ordinary people more generally), or risk being simply wrong. A Midwife’s Tale’s scholarly innovations have carried its influence beyond these specific fields and has given Martha’s story global reach.

To read the book, click: A Midwife's Tale: The Life of Martha Ballard, Based on her Diary, 1785 - 1812 by Laurel Thatcher Ulrich.

And, again, for the film, please click HERE

For a listing of some other fairly accurate American history movies, check out THIS post.

From the site DoHistory about the information on the filming of "A Midewife's Tale":

Copyright © 2000, President and Fellows of Harvard College.

All materials are copyrighted by the President and Fellows of Harvard College except where otherwise indicated. Commercial use prohibited without permission. All rights reserved."

I hope you enjoy it. And if you do, I hope it entices you to purchase "A Midwife's Tale" in both book and film form.

You will not be sorry.

Shortly after beginning the

project of making A Midwife's Tale - the diary of Martha Ballard - into a film, producer Laurie Kahn-Leavitt put together a board of advisors who were/are expert on the

eighteenth century: on women's history, architectural history, medical history, music, and material culture. With their guidance, she plunged into the research, which included visiting the buildings which are still standing that were part

of Martha Ballard's world. She visited archives all over Maine, Massachusetts, and New

Hampshire and put together a database of thousands of images from the

eighteenth century, including handwritten documents, paintings, maps, medical

book illustrations, children's book illustrations, newspapers, broadsides, photos of buildings, and the artifacts of everyday life. She found out what had

been written about dialects and music and religious beliefs two hundred years

ago, and she learned as much as she could about the everyday work done by men

and women in eighteenth century Hallowell, Maine: textile production, laundry, cooking, farming, surveying, etc. Kahn-Leavitt also put together a timeline of

Martha Ballard's life and the national and international events that affected her

family and her town.

Working closely with Laurel Ulrich, the book’s author, Kahn-Leavitt developed a script.

They auditioned local stage actors, offered them a free workshop, created a small ensemble, and got to work in a

barn in Lincoln, Massachusetts (loaned to them by the Society for the

Preservation of New England Antiquities). The actors were able to improvise

lines.

|

| Real people - not actors - were cast to play the roles. Hence, another reason why this film plays out so naturally; actors almost always tend to, shall we say, over-act...become scripted. |

Historical issues involved in the recreation of the past came up;

questions about behavior and speech kept coming up, and many were unanswerable

given the documentation that survives. How did these people speak? What songs

did they sing to themselves? How close did they stand to one another? They

realized how far they needed to venture beyond the solid ground where

historians feel most comfortable -- a rather frightening realization for them. Laurel Ulrich was present for nearly all of the dramatic shooting days. Eighteenth century dance expert Richard Castner taught the cast several

eighteenth century dances for the quilting dance that precedes the three

marriages in the film. Medical historian Worth Estes was present the day the

workshop shot the dissection of Martha's niece, Parthenia. And other project

scholars were consulted by phone as needed.

Difficult concrete historical questions arose when preparing to

put Martha's physical world up on the screen. When Martha applied onions to the

feet to draw out a fever (something learned from her diary), were they raw or

cooked? Did she apply them to the top of the foot or to bottom of the foot? Medical scholars didn't know, so they asked several modern herbalists and were

told they used raw onion on the ball of the foot. Did Martha say "Mistress" or "Misses" for the written "Mrs" in

her diary? It is known this period was a time of transition between the two

pronunciations. But which would Martha use? It was feared modern audiences

would incorrectly associate the use of "Mistress" with a relation of

servitude, so they decided to go with "Misses." Kaiulani Lee, the

actress playing Martha, asked during a scene in which she is called in to help

the Rev. Mr. Foster, who is sick with scarlet fever, "Do I roll up his

sleeve? Do I look in his throat? Or do I keep a more respectful distance?" The answers received from historians on the subject were split. Most of the men

felt that Martha would keep her distance. Most of the women felt that Martha

would have inspected the minister. So it was shot both ways, and the final

decision was made in the editing room.

All involved knew A Midwife's

Tale would sink or swim with the casting of Martha Ballard. The character

of Martha Ballard was a very non-modern combination of warmth and reticence. They

auditioned many accomplished, first-rate actresses. But something interesting

happened. The actresses who understood the warmth in Martha's character tended

to tip into sentimentality. And the ones who understood the reticence in her

character tended to tip into cool detachment. Kaiulani Lee, however, nailed the

part when she auditioned.

She is talented, and strong, and remarkably expressive in her physical movements. For a script like what was needed, she was perfect. The only reservation was her age, but they ultimately handled that by splurging on special effects makeup artists flown in from LA.

The producers also had to create a believable family and a believable town. They were looking for people who looked like they had worked with their hands their entire lives. They wanted to create a past that was convincing-- a world in which people had different shaped noses, and bad teeth, and birthmarks, and other human imperfections. And they were wary of child actors trained to hawk products by being cute.

She is talented, and strong, and remarkably expressive in her physical movements. For a script like what was needed, she was perfect. The only reservation was her age, but they ultimately handled that by splurging on special effects makeup artists flown in from LA.

The producers also had to create a believable family and a believable town. They were looking for people who looked like they had worked with their hands their entire lives. They wanted to create a past that was convincing-- a world in which people had different shaped noses, and bad teeth, and birthmarks, and other human imperfections. And they were wary of child actors trained to hawk products by being cute.

Early on, the decision was made to

shoot A Midwife's Tale in real locations because building sets from

scratch would be too expensive, and the first step was to find a single place

where they could shoot the dramatic scenes for the film. The director Dick

Rogers, the production designer Nancy Deren, and producer Laurie Kahn-Leavitt

scouted locations all over Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, and

upstate New York. But there was no single place that had a wide river like the

Kennebec (the river that runs through Hallowell/Augusta Maine), a functional

eighteenth century sawmill, a variety of farmhouses and outbuildings, fields, and forest. When the architectural advisor said he'd heard about, but never

visited a place called King's Landing in New Brunswick, Canada, the three made

the trip and were amazed; King's Landing (a settlement which includes houses

built by Loyalists escaping the American Revolution) had a wide river, a

sawmill, lots of buildings, outbuildings, fields, animals, and woods.

They felt they had walked onto a $30 million set that was almost (but not quite) designed with the film in mind!

|

| Filming A Midwife's Tale |

They felt they had walked onto a $30 million set that was almost (but not quite) designed with the film in mind!

To get correct period clothing for A

Midwife's Tale, they looked at images of everyday life in American and

European paintings and engravings from the period. They also looked at

photographs of 20th century rural life and photographs of the Colonial Revival –

also from the early part of the 20th century. They used these images with

caution, since the Colonial Revival often romanticized the past, and modern

rural life is different in many ways than it was in Martha's time. But valuable

lessons were gleaned from all of these images -- about the quality of light, the kinds of disarray or tidiness in a rural home, the look of smoke-stained

walls, the kinds of objects typically left on mantle pieces, and hundreds of

other details. Together the director, DP (director of photography), and

production designer chose the palette for specific scenes and sets. Director

Dick Rogers and DP Peter Stein conducted experiments with different kinds of

lighting. Working with Dick and Peter, production designer Nancy Deren drew up

ground plans showing how the buildings and gardens at Kings Landing could be

adapted to match the script and enhance Dick's directing choices. Meanwhile, costume designer Kim Druce coordinated her costume plans with their choices, and drew up costume sketches.

On filming A Midwife's Tale, everything

had to age over the twenty-seven year time span covered in the book: the

buildings, the props, the costumes, even the actors and the seasons had to

change.

Production designer Nancy Deren

oversaw an art department that included carpenters, painters, gardeners, set

decorators, and set dressers. They built fake fireplaces, fake walls, and fake

moldings when the real buildings at Kings Landing were not historically

appropriate for Martha's world. They painted fake smoke stains, they planted

fake gardens, and they transformed existing spaces in remarkable ways. A

cavernous barn, for example, was transformed into two sets: it became the

Hallowell Congregational Church for one scene, and then it became the store at

Fort Western in another scene!

|

| Looks like natural lighting instead of the bright lights of Hollywood to me! |

Furniture and household objects were borrowed from Kings Landing

and other generous museums and historical societies all over New England. The

prop department created replicas of Martha's diary booklets, of period

newspapers, children's books, medical kits, and maps. A boat ride was faked

using a pickup truck and smoke machines. And "rain" was created using

garden hoses and fire trucks.

In a period piece like A Midwife's Tale, costume, hair and makeup

require extensive research. But you have to use the historical sources

carefully. Looking at the portraits that survive from the period, you

see the top ten percent of the population dressed up in their finest clothing, with many of their imperfections "improved" by the portrait painter. To figure out what the other ninety percent of the population might have looked

like (on days when they did--and did not--look their best), the costume, hair, and makeup departments all had to extrapolate (expand on their knowledge). How would most of the population

adapt the styles of the day to their budgets? Which fashions were they aware

of? Using information about 18th-century shipping and trading patterns, guessing about each individual character's feelings about fashion, and making

inferences about personalities, the costume, hair, and makeup departments

created a range of characters to inhabit the film's world. Some of Martha's

family and neighbors (as portrayed in the film) attempted to keep up with the

latest fashions. And others were decidedly old-fashioned in their choices. Some

were quirky in their tastes. Others were strictly conventional.

Because they knew that the film would flop if the audience was aware of

old-age makeup that was not convincing, this was one place they paid

careful attention. Kaiulani was actually in her forties, but she had to age in

the film from 50 to 77 years old. To age her and the other principal actors in A

Midwife's Tale, they brought in special effects makeup artists from L.A. For the final scenes of the film, Kaiulani had to spend three hours in makeup

getting her face and hands made old.

|

| Actual newborn babies were cast as... well...newborns! |

Early on, the decision was made to

use music sparingly, taking advantage of tunes and instrumentation that belong

in Martha Ballard's world. The advice of several experts who know about

18th-century American religious music and popular music was sought out. They

recommended a wide range of tunes and songs, and some were written into the

script, performed or sung by the film's actors: a lullaby, a religious fugue, two drinking songs, and a marching tune.

Along with the music, most of the

sound effects in A Midwife's Tale were natural sounds of rural animals, insects, wind, rain, etc.

With the film's completion, it was the producer's job to launch the finished work into the world, spreading the word, and finding the best

distributor for the film. In the case of A Midwife's Tale, there were multiple audiences to reach: professional

historians and history buffs, healers and midwives, people interested in the

history of medicine, senior citizens, fans of the book, and people who want to

know more about women's lives in the past. Screenings were held with all of

these audiences. And the film received coverage nationwide in newspapers, magazines, radio, and TV.

On

January 19, 1998 it was broadcast as the opening show of the tenth season of

the PBS series THE AMERICAN EXPERIENCE. It is now available through PBS Video and Amazon.com (click HERE), and

is used by schools, universities, museums, health, and community groups around the world. <<<

From the social historian to the casual history buff, from the living historian & reenactor to the historical presenter - all who want to see real history come to life on their television screens should make watching A Midwife's Tale a priority.

Don't you just love watching history when they finally get it right?

(Side note: Clara

Barton, Civil War nurse and founder of the American Red Cross, was the granddaughter of Ballard's sister, Dorothy Barton).

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

From THIS page, I nick'd this "character" information about Martha's children:

Cyrus Ballard

Martha’s oldest son. Quiet and unmarried, Cyrus follows miller jobs wherever they become available and moves in and out of his parents’ house until he is in his early forties. Having developed powerful shoulders through his years of re-chiseling mill stones, Cyrus is a great help to Martha whenever he is in town. Though no mention of it is made in the diary, Ulrich theorizes that Cyrus had great difficulty achieving independence due to some sort of mental impairment.

Jonathan Ballard

Martha’s middle son. Jonathan is brash and drinks too much, and his fits of temper are a source of contention between him and Martha for much of her life. On more than one occasion, Martha records fights that Jonathan has instigated with neighbors, and though the rest of the family learns to accept these brawls, Martha’s descriptions indicate that she remains opposed to his behavior. Despite his temper, Jonathan is very aware of his responsibilities. He marries Sally when she gives birth to his child, and he makes sure his mother is taken care of even if it isn’t in the way she might have wanted. Jonathan has occasional problems with debt but works hard to raise the fortunes of himself and his children.

Hannah Ballard Pollard

One of Martha’s daughters. A quiet, dutiful girl who masters all of the domestic skills necessary to set up a good household of her own, Hannah is the only daughter living at home during the course of the diary who isn’t mentioned in conjunction with directly helping with her mother’s nursing duties. After her marriage to Moses Pollard, Hannah’s focus seems to be on her own large family. Still, Hannah’s birth so close to the death of her sisters may have led to a special relationship between her and Martha, as she is the only child listed at Martha’s bedside in the diary’s final entry.

Dolly Ballard Lambard

Martha’s youngest daughter. The only daughter to develop a specific career of her own, Dolly trains and begins working as a dressmaker for a period of time before her marriage to Barnabas Lambard. Dolly is a hard, uncomplaining worker, and she assists her mother during her midwiving and nursing duties, though she is not always sympathetic enough to Martha’s needs. Dolly is left in charge of Martha’s papers after she dies, and she passes the diary on to her daughters.

Martha’s diary is passed down through Dolly’s descendants until it reaches Martha’s great-great-granddaughter, Mary Hobart, one of the country’s early female physicians. Mary treasures the diary but gives it to the Maine State Library in 1930 so that it might be more accessible to historians.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

~“Clear and spring like. Grew cold at Evening. Snowd some. I have been at home. Irond my cloaths &c.” - Martha Ballard~

Laurel managed to extricate a stunning vision of one woman’s life from such cryptic passages and show us that viewing the world through the writings of one woman in a remote corner of the globe could spur fundamental reassessment of long-established narratives. Laurel saw in this (large) but not especially inspiring cloth-bound diary a promising resource that other historians had failed to appreciate fully. It also demonstrated that economic, medical, legal, religious, and demographic histories need to understand the experiences of women (and of ordinary people more generally), or risk being simply wrong. A Midwife’s Tale’s scholarly innovations have carried its influence beyond these specific fields and has given Martha’s story global reach.

Because of the research time spent in writing this book, Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, a truly gifted historian, was able to bring to life an 18th century woman to the extent that one can almost hear the voice of Martha Ballard

as she goes about her productive, meaningful life in late 1700s Maine. One can almost

feel her shining, transcendent spirit nearby...

And, again, for the film, please click HERE

Here is a snippet from the beginning of the film:

For a listing of some other fairly accurate American history movies, check out THIS post.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

From the site DoHistory about the information on the filming of "A Midewife's Tale":

"In general, the content on this site

is shareable and can be used for personal and educational uses without

restrictions. As always, proper citing and due attribution is required. Linking

to this site from your website is permissible. For use in publications, papers

and other uses, please cite as follows, including specific information on the

title, url, and date accessed:

"History Toolkit: Using Primary

Sources," Do History

http://dohistory.org/on_your_own/toolkit/primarySources.html (accessed April

28, 2009). Reprinted with permission from the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History

and New Media, George Mason University.Copyright © 2000, President and Fellows of Harvard College.

All materials are copyrighted by the President and Fellows of Harvard College except where otherwise indicated. Commercial use prohibited without permission. All rights reserved."

~ ~ ~

ReplyDeleteExcellent Ken!!!

I really enjoyed this whole writing :-)

And the photo of you, and of Patty at the walking wheel in the

home of Samuel and Anna Daggett, is a first prize winner!!

(worthy to be printed on canvas and hung on the wall)!!

Blessings and warmth Linnie

Thanks Ken! I was one of the extras in the church scene (along with my 9 month old son) and last birthing scene. The curatorial staff at Kings Landing were determined to get it right and one became my mentor and I remember what she taught me when I myself was in charge of curatorial advice on other movies shot at Kings Landing.

ReplyDeleteThank you so much Ken, this review is brilliantly done! I have had this on my films to buy for awhile and forgot about it. I remember seeing this on PBS-dark is what I remember, yet there was triumph:-)

ReplyDeleteSharing to Take Peace , so others can enjoy.

Cheers,

Suzanne

Thank you so much for this in depth "movie review". I'm very familiar with the book but never knew there was a movie. I ordered a copy and look forward to watching it.

ReplyDeleteDo you happen to know more about the barn in Lincoln, Massachusetts mentioned above? I live in Lincoln and am a reenactor here.

I live in Augusta, Maine, formerly Hallowell. I've read the book and have seen the movie. Laurel Ulrich spoke at a conference here, when the movie first came out,

ReplyDeleteand seeing the movie was part of it.

The story, the book, and the movie are all fabulous.

I know it's been 8 years, but this article plagiarises heavily from the site DoHistory.org, without proper citation. I clicked on here hoping for an indepth review of the film, and was saddened to see so much material copied and slightly modified instead of original work.

ReplyDeleteKen, I'm disappointed in you

Plagiarize, by definition, means "to take (the work or an idea of someone else) and pass it off as one's own."

ReplyDeleteI did not claim this work to be my own...anywhere.

If you look at the bottom of the post, I cite the article exactly in the manner that was asked. In fact, I copied and pasted what they wanted. I sent them the post with no negative response. In fact, in the post itself, I also state exactly where the information came from, so it is in there twice.

Methinks you need to double check - all done correctly and legitimately without question - just as they asked me to do.

I'm sorry you are disappointed, but it is there...twice.

No plagiarisms at all, and I am offended of this accusation.