The printed paper is on its way out. Technology is ruling newspapers, which is pretty much considered outdated and very "old school." But...this isn't the first time technology has reared its ugly head!

Reading the writing of the past can sometimes be confusing and rather difficult. In fact, there are many today who cannot even read the handwriting (as we used to call it - it's known as "cursive" today) from as recent as the 1960s and '70s, much less from 200+ years ago.

But there was a time when the printed newspaper and broadsides were very popular, though I'm not sure if they were ever truly respectable (lol).

Still, they were widely read.

Going back even further, like to the early 19th century and before, one of the most confusing letters in the alphabet is the Long S - you know, the letter that looks like a small f but is actually an s?

It is confusing for many who like to read the old 18th century type, but once one can understanding its place, it will all begin to somewhat make sense - it did for me and became much more, shall we say, readable.

Hopefully today's posting can help you as well.

..............................................

Before Johannes Gutenberg introduced Europe to the movable-type printing press in the 15th century, block (or elementary) presses were employed. For instance, books were created using a block printing method, where characters and images were carved into a wooden block and then pressed on paper. Block printing proved to be time consuming and expensive because each page was individual.

The 18th century printing process itself was not much different than it was in the era of Gutenberg, as printers used the old hand-press device, though with movable type. Rather than manually carving an individual block to print a single page, movable type printing allowed for the quick assembly of a page of text utilizing individual letters. Furthermore, these more compact type fonts could be reused and stored.

Basically, the press worked with two main components: a screw and a movable bar. The different blocks of type, which contained the text, were put inside frames (called coffins), and those coffins are placed on wood or stone beds and then moved in and out by hand with the lever of the press. Gradually, improvements have been made in the process, though nothing too tremendous, which speaks to the quality of the original design. Hardly any significant changes were made until 1798 when the Earl of Stanhope made a frame out of cast-iron instead of wood, which had been used in centuries previous. In the wake of these small improvements, however, the printing process itself still remained quite simple and basic: make the type from the submitted text, cut the paper and put it under the press, do the actual pressing, and then you have printed text.

And, then again, the printing process from the 18th through much of the 19th century showed no great dramatic change. It seems it wasn't until the very late 19th century before we saw any sort of dramatic changes to the printing press itself, when the automatic typesetting machine was developed.

|

| Original prints from 1770 (click to enlarge) |

We do need to understand that the folks who lived in the later colonial period were more informed than many in our modern age give them credit for. Similar to the taverns from that time, the printing office was a center of local and imperial communications, though it was the broadsides and newspapers which provided a way to exchange information and events between the thirteen colonies rather than by word of mouth from the traveler, keeping people informed of major events, influenced public opinion, and, yes, playing a significant part in the decision to declare independence from Great Britain. According to Todd Andrlik in his wonderful book, Reporting the Revolutionary War: "We live in a time of instant and on-demand news. Journalists and bloggers work frantically around the clock, competing to break news stories before anyone else. Cable news channels and websites stream updated headlines nonstop across their screens. Using Twitter and Facebook, millions of citizen reporters scramble to share the latest news affecting their lives, practically in real time. Despite the debated endangerment of printed papers, it is difficult to imagine a time when media were more important. However, 250 years ago, newspapers were the fundamental form of mass media and were more important than in any other time in America's history."

So, I researched to have an idea of how a colonial printer's shop, such as the ones owned by famed printers of the Declaration of Independence, John Dunlap in Philadelphia or Benjamin Edes & John Gill in Boston, worked to prepare to print.

The letters used for printing are first hand-carved in steel, then punched in brass and sanded to achieve the same depth on every character. Then, they are cast in lead, and the finished characters are stored in precisely organized cases; the terms "upper case" and "lower case" originated from these wooden cases. Quickly and correctly picking letters out of the cases became second nature by necessity – it would take far too long to closely examine each letter to make sure you had chosen an "e", not a "c".

Now, the following, taken from the Colonial Williamsburg pamphlet "The Apprentice," explains in an easy and concise manner what it was actually like to prepare and print:

The compositor (one who sets the type for printing) took one letter (or character) at a time from the cases in which the type was stored to create the words & sentences on a composing stick. When a paragraph was completed, he transferred it to a wooden tray called a galley. The type would then be slid onto a flat, marble stone and secured the type in an iron frame called a chase. The prepared type would then be carefully carried to the printing press. If he accidentally dropped the chase, many hours of work would be lost.

|

One of the printers being used to recreate authentic replications of Gill's Boston edition of the Declaration of Independence. (Picture courtesy of the Printing Office of Edes and Gill) |

A worker called the beater would then rub two leather-covered balls with ink made of linseed oil, pine resin, and soot. The puller would then give a good, strong smooth yank on the bar of the press to force the paper onto the inked type below.

|

Working together, the beater and the puller could print 200 sheets in an hour. (Picture courtesy of the Printing Office of Edes and Gill) |

It was painstakingly setting the type that took the longest for the printer.

I can only imagine what the colonial printer would think of our printing process today.

Gary Gregory is the Executive Director, Print Master, and founder of the recreated Edes & Gill printing shop in Boston, as well as the company known as The History List. There is only one original copy of the John Gill 1776 version of the Declaration of Independence that still exists and was located in the collection of the Bostonian Society by Gary. He then had all 9.000 characters of type meticulously cast in lead to match the original document.

This true recreation was then printed by hand at the historic Printing Office of Edes and Gill on July 3rd 2012, on the ancient Wooden Common Press using 100% cotton linen, very-fine crane laid paper, marking the first time since July 1776 that anyone had printed the Boston Broadside of the Declaration of Independence.

Opening its doors to the public in 2011, the new version of the Printing Office of Edes & Gill is considered Boston’s only printer still doing the job in the old colonial ways, and is located in the historic Clough House, built in 1712, and is part of the Old North Church Historic Site in Boston.

Gary trained with master printers at Colonial Williamsburg before bringing his craft to Massachusetts, first at the Museum of Printing in North Andover, and now at the Printing Office of Edes & Gill. He is meticulous in his work and highly knowledgeable from a combination of years of research and hands-on experience. Printing reproductions of historical documents comes down to the miniscule details, sometimes quite literally; picking the correct font size, for example, or deftly spreading a very small amount of ink over a large surface of type.

|

The type is set for the Boston edition of the Declaration of Independence. Meticulously historical in every way. |

The video is Gary printing the Constitution - I cannot find the video of him printing the Declaration on You Tube. But the process is the same:

|

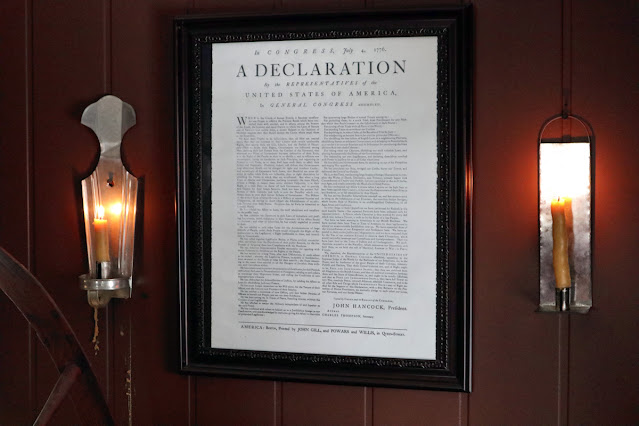

I was so impressed that copies of the Declaration were being printed individually on a period printing press, that I naturally purchased a copy for myself. (Above picture courtesy of the Printing Office of Edes and Gill) It now hangs framed in my parlor... I am very proud to own such a copy. |

Printers, in many cases, had to make their own paper - not an easy process - and though the paper production took several months, the result was a quality that can last for hundreds of years.

|

| 18th century paper-making process in a nutshell~ |

The following information on making paper came directly from THIS page/blog:

The first stage in the papermaking process was to select the material from which the paper was going to be made. In the eighteenth century, this would typically have been cotton and linen rags.

Having selected the material, the next step is to break it down, making it into a pulp. When papermaking was first introduced in Europe in the twelfth century, rags were wetted, pressed into balls, and then left to ferment. After this, the rags were macerated (softened) in large water-powered stamping mills. In the eighteenth century, a beating engine (or a Hollander), was used to tear up the material, creating a wet pulp by circulating rags around a large tub with a cylinder fitted with cutting bars.

|

| Actual 18th century paper. |

Having been broken down, the liquid pulp mixture is then transferred to a container. In the eighteenth century, someone known as the ‘vatman’ would have stood over this container and dipped a mould into the solution at a near-perpendicular angle.

Turning the mold face upwards in the solution before lifting it out horizontally, the vatman would have pulled out the mold to find an even covering of macerated fibers assembled across its surface. It is these fibers that would later form the finished sheet of paper.

The molds used in papermaking determine several features of the finished sheets of paper, including shape, texture, and appearance.

After the mold was pulled from the vat, the eighteenth-century vatman would pass it on to a coucher who would remove the sheet from the mold, before pressing it between felts to remove the water.

At this point in the eighteenth-century process, sheets were ‘sized’—dipped into a gelatinous substance made from animal hides that made the sheet stronger and water resistant.

After having size applied, sheets in an eighteenth-century papermill would have undergone a number of finishing stages. These included polishing and surfacing, processes that gave the paper a more uniform appearance.

It is after these final finishing and drying processes that sheets of paper are ready to be packaged up and sent to the stationer’s.

|

| No, Caslon is not a new font whatsoever! |

Many printers by mid-century used a popular typeface (font) called Caslon. William Caslon I was an English gunsmith and designer of typefaces. Around 1720 he created an extended set of serif typefaces known as Caslon. Benjamin Franklin, who, as you may know, was a printer himself, liked the Caslon fonts so much that he hardly ever used any other typeface. Ironically, most of the type used by Philadelphia printer, John Dunlap, to compose the Declaration of Independence on the night of July 4, 1776 was likely from the Caslon type foundry – a British company, and later “letter-founder to the King.” In fact, the 1785 Caslon specimen book was even dedicated to King George III – the same King that the American colonists were declaring independence from!

But there was one letter in this font (and the others of the time) that confuses many modern folk of today: the "long S" - you know...the 's' that looks like an 'f'?

|

| See the long S? |

Let's be honest - unless one is used to reading 250 year old documents, American colonial handwriting and printing can look strange to many. But if you want to understand or imitate colonial handwriting, then using those long S's correctly is the most obvious thing to understand. In colonial printing 'fonts,' one can easily tell the "s" from a printed "f" by the little cross-bar being only on the left-hand side, or may not be there at all. In colonial handwriting (or cursive), the "long s" is written like an "f," except the bottom loop is written clockwise instead of counter-clockwise.

By the way, the "long s" wasn't used randomly.

Here are the rules for when to use it or help to understand how it's used in colonial handwriting:

Use the "long s" at the beginning and middle of words, but use the regular "s" for the last letter of a word.

If there are two s's together, use the "long s" for the first one and the regular "s" for the second one. Use the regular "s" before and after the letter "f" (the real letter "f"!)

Use the regular "S" whenever the "S" is uppercase, like at the beginning of a sentence.

Here is an original example of the colonial style of writing:

It's really not too difficult. It just takes a little getting used to.

Here are a few more examples of the Long S:

| ||

| An italicized 'long s' used in the word "Congress" in the United States Bill of Rights from 1789.

|

|

| Old style Caslon |

It was in late 18th century London when John Bell, the founder of a newspaper called The Morning Post, switched from the long s to the more-familiar-to-us short one.

Printers in the United States stopped using the long s between 1795 and 1810: for example, acts of Congress were published with the long s throughout 1803, switching to the short s in 1804. In the US, a late use of the long s was in Low's Encyclopedia, which was published between 1805 and 1811.

The change may have been spurred by the fact that the long s looks somewhat too much like an 'f' (in both its Roman and italic forms), whereas the short s did not have the disadvantage of looking like another letter (aside from its capital form), making it easier to read, especially for people with vision problems.

Or reading by candlelight.

|

| Strictly by candle light. |

My friends, understanding how life worked in long ago past, including the way the long S was used helps in visiting a museum.

What life was like.

As I wrote in this blog with the title, "It's the Little Things: Shadow Portraits, Bourdaloues, Revolutionary Mothers, and Other Interesting Historical Odds & Ends," and this one called "Heating Stoves and Wall Pockets: Items That Made A House A Home", it truly is the small mostly unnoticeable things that brings the past to life in a very effective manner, for it is the everyday things in our own lives and homes that will bring future memories with smiles. Such as how we get our news, how we write our news, and how we spread the news.

Then we will remember things we know today.

Speaking of news, I have a bit here:

~On March 8, 2023, around 9:00 pm, I had my 2,000,000 visitor to Passion for the Past!

I never in my wildest dreams would ever have thought I'd have that many visits.

I am humbled.

Thank you.~

.... .... ....

Until next time, see you in time.

Another source came from HERE

Other posts that might interest you:

The printing of the Declaration of Independence, click HERE

Museum in a book books, click HERE

History books, click HERE

Time Life History books, click HERE

Music from the past, click HERE

~ ~ ~

Congratulations on the 2M visits, Ken! You know I am a big fan of your bog. It is my favorite History themed blog of all time.

ReplyDeleteThank you so much! Truly---I thank you!

ReplyDelete