|

| The Hannah Barnard Court Cupboard: 1710 - 1715 |

Hannah was a young woman of around 20 when a major event occurred very near to her: during Queen Anne’s War (the second in a series of French and Indian Wars fought between England and France), an uprising known as the Raid on Deerfield (or the Deerfield Massacre) took place on February 29, 1704. The French and local Indian forces attacked the nearby English frontier settlement of Deerfield, Massachusetts just before dawn, burning part of the town, killing 47 villagers, and taking 112 settlers captive to Canada, of whom 60, including John Marsh (a Hadley soldier who would become Hannah's husband a decade later), were eventually brought back.

It was in 1715 that Hannah, at the age of 31, married this man, John Marsh. Hannah was John's 2nd wife, for his first died (along with a young child the two had) some years earlier.

There are questions on why Hannah married at an age that was older than most first marriages for women. Perhaps it was because she assumed the role of "keeper" of her father's house after her mother had died in 1709. Or maybe she became a teacher in nearby Deerfield, though there is no record of this.

Maybe she just wasn't quite ready to leave her family.

|

| A side view of the cupboard |

Maybe she just wasn't quite ready to leave her family.

No matter, she must have been pretty special to someone close to her, however, for

sometime between 1710 and 1715 the court cupboard shown in the pictures here, complete with her name

scrolled upon it, was built for her. This was a highly unusual practice

at the time, for women generally didn't 'own' anything.

Did her father have it made as a dower or perhaps as a wedding gift, or maybe even as a gift for helping as she did after his wife's death?

Or how about the possibility that her husband might have had it made for her after they were wed, though this, in my opinion is improbable for I would venture to guess he would not have had her maiden name embossed upon it, but rather her married name instead.

Perhaps after thirty one

years as a Barnard, Hannah did not want to forget her family name as she

entered into marriage. Or maybe it marked the fact that Hannah was

well aware that while women could not inherit property, they could inherit

movable furniture. Did she ask

that her name be painted there? Or was she surprised when she received it from

her family or her betrothed?

My own opinion is that it was made for her before she was even betrothed; quite possibly, from her father as a gift.

But that's just my opinion.

In researching about the term "movables" (as mentioned above), I learned these were items that could be moved from one dwelling to another easily. While most males usually received property as a gift or from a will, females received movables as part of a dowry or given as gifts or from a will, for it was the woman that was expected to "move" after marriage, not the man. In such a system, women themselves became "movables," changing their names and presumably their identities as they moved from one male-headed household to another.

Did her father have it made as a dower or perhaps as a wedding gift, or maybe even as a gift for helping as she did after his wife's death?

Or how about the possibility that her husband might have had it made for her after they were wed, though this, in my opinion is improbable for I would venture to guess he would not have had her maiden name embossed upon it, but rather her married name instead.

|

| The other side |

My own opinion is that it was made for her before she was even betrothed; quite possibly, from her father as a gift.

But that's just my opinion.

In researching about the term "movables" (as mentioned above), I learned these were items that could be moved from one dwelling to another easily. While most males usually received property as a gift or from a will, females received movables as part of a dowry or given as gifts or from a will, for it was the woman that was expected to "move" after marriage, not the man. In such a system, women themselves became "movables," changing their names and presumably their identities as they moved from one male-headed household to another.

The

colorful hearts, petal flowers, vines, and half-circles are characteristic of a

number of "Hadley-chests" made around Hadley, Massachusetts nearly

three centuries ago. Six of them include women's names painted on the front, such as this. It is unusual for a piece of furniture to be decorated with

anyone's name, much less a woman's.

It is unfortunate to learn that Hannah died a year after her marriage while giving birth to a daughter named Abigail.

After Hannah's death, John Marsh married again and had four more children with his third wife. He was only in his forties when he himself died in 1725. His will gave only his then two year old son all of his real estate, though it was specified that Abigail was to receive 120 pounds "to be paid in what was her own Mothers," plus "her Mothers Wearing Cloaths...to be given her free."

The younger daughters of John Marsh received portions worth 100 pounds.

John Marsh had one child who died at an early age with his first wife, one child with Hannah, and four with his third, and his will shows this. The movables were divided into a general list as well as two sub-categories labeled "3d Wives Goods" and "2d Wives Goods." The general list contained a "carved work chest" valued at 30 shillings. This is thought to be from his first wife. Hannah's list included a "flowered Chest" valued at thirty two shillings.

Presumably, the more valuable of the chests was the court cupboard that survives today (and is pictured in this posting). At thirty two shillings it certainly was worth as much as most cupboards.

Abigail Marsh married Waitstill Hastings, and in 1742 had a daughter of her own. But she didn't just name her Hannah (after her mother), but Hannah Barnard Hastings! Since the use of middle names was rare in New England in this period, this was an obvious purposeful choice. Of course, this Hannah inherited the cupboard. The name persisted for two more generations: in 1769, Hannah Barnard Hastings married Nathaniel Kellogg, and the following August she had a daughter whom she named for her long-dead grandmother (and herself). This third Hannah died in 1787, but in 1817 her brother honored both his sister and his mother by naming a daughter Hannah Barnard Hastings Kellogg. This Hannah's migration to California broke the link between the cupboard and its history.

There seems to be a blank space from that point to 1934 when the cupboard was featured in Antiques Magazine. The author of the article stated only that the cupboard belonged to "an ancestress of a later owner." But because of the name Hannah Barnard was emblazoned upon it, the cupboard's history was that much easier to trace.

This wonderful piece of Americana now sits in a well-viewed and honorable area inside the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan, along with historical furniture pieces once belonging to the mother of George Washington and Mark Twain's drop leaf table.

Now, let's look at a similar item from a different perspective (although it was purchased and not made):

I have a dresser - a well made dresser - that my parents bought for me and my brother when we were both very young. It was purchased probably around 1967 or 1968 or thereabouts. It still resides in my house in my bedroom, now used by my wife for her clothing. This wonderfully made piece of furniture still looks *almost* as good as it did when bought brand new over 50 years ago.

It is unfortunate to learn that Hannah died a year after her marriage while giving birth to a daughter named Abigail.

After Hannah's death, John Marsh married again and had four more children with his third wife. He was only in his forties when he himself died in 1725. His will gave only his then two year old son all of his real estate, though it was specified that Abigail was to receive 120 pounds "to be paid in what was her own Mothers," plus "her Mothers Wearing Cloaths...to be given her free."

The younger daughters of John Marsh received portions worth 100 pounds.

John Marsh had one child who died at an early age with his first wife, one child with Hannah, and four with his third, and his will shows this. The movables were divided into a general list as well as two sub-categories labeled "3d Wives Goods" and "2d Wives Goods." The general list contained a "carved work chest" valued at 30 shillings. This is thought to be from his first wife. Hannah's list included a "flowered Chest" valued at thirty two shillings.

|

| Imagine what this cupboard has "seen." |

Abigail Marsh married Waitstill Hastings, and in 1742 had a daughter of her own. But she didn't just name her Hannah (after her mother), but Hannah Barnard Hastings! Since the use of middle names was rare in New England in this period, this was an obvious purposeful choice. Of course, this Hannah inherited the cupboard. The name persisted for two more generations: in 1769, Hannah Barnard Hastings married Nathaniel Kellogg, and the following August she had a daughter whom she named for her long-dead grandmother (and herself). This third Hannah died in 1787, but in 1817 her brother honored both his sister and his mother by naming a daughter Hannah Barnard Hastings Kellogg. This Hannah's migration to California broke the link between the cupboard and its history.

There seems to be a blank space from that point to 1934 when the cupboard was featured in Antiques Magazine. The author of the article stated only that the cupboard belonged to "an ancestress of a later owner." But because of the name Hannah Barnard was emblazoned upon it, the cupboard's history was that much easier to trace.

|

| The Barnard family tombstone located in the Old Hadley Cemetery: HANNAH HIS DAUGHT DYED ON SEPT YE 31ST 1716 AGED 32 YEAR Yes, it does say "Dyed on Sept 31 1716." September 31?? Hmmm... (photo courtesy of "Find A Grave") |

Now, let's look at a similar item from a different perspective (although it was purchased and not made):

|

| ~My dresser from the mid-1960s~ I have no idea what the specks you see on the lower left are from, but they are permanently embedded in the finish. That's okay - I'm sure it was from my brother or I and it adds to the over-all history of the piece. |

Nothing special - neither my brother nor myself will be known, perhaps, by anyone in the future aside from our own family or family historian.

Another story:

Another story:

for Christmas of 1982 my mother bought me a desk - a basic but beautiful wooden writing desk made of high quality workmanship - and it actually has almost a colonial feel to it. Let me tell you, I used this thing, which was covered with papers and pens & pencils & erasers back in those days long before the home computers took over, to write my stories, do research, and even sometimes just to settle back to read my books. I still have it, only now the desk is being used by my son.

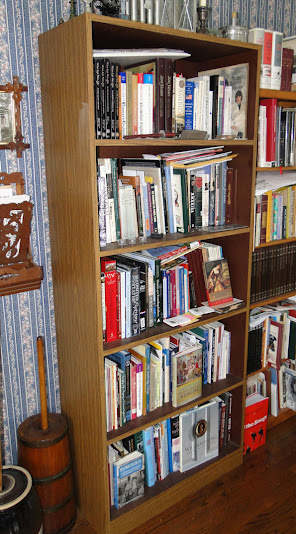

Back in 1983, I had a shelving unit made by my brother's carpenter friend to specifications I gave him for my record album collection. Since that time I've sold nearly every one of my albums (excepting my Beatles collection and a few very cool country/bluegrass records), and now I, instead, have hundreds of history books sitting atop of the shelves.

I also have my grandpa's wall clock, which was made in the late 1800s, and my grandma's Singer sewing machine from 1920 (a wedding gift to her from my grandfather). Family heirlooms passed on to me and, one day, to my own children...and hopefully to my grandchildren as well.

Yes, I do consider my dresser, desk, and shelving unit to be heirlooms right along side of the clock and sewing machine; I don't plan to get rid of any of them and, as I said, hopefully they will be passed on to my descendants.

|

| My record shelf turned book shelf from 1983 |

I also have my grandpa's wall clock, which was made in the late 1800s, and my grandma's Singer sewing machine from 1920 (a wedding gift to her from my grandfather). Family heirlooms passed on to me and, one day, to my own children...and hopefully to my grandchildren as well.

Yes, I do consider my dresser, desk, and shelving unit to be heirlooms right along side of the clock and sewing machine; I don't plan to get rid of any of them and, as I said, hopefully they will be passed on to my descendants.

Remember - - - family heirlooms.

Now, look around you. Look at your own belongings.

Do you think that anything you own in your house will still be around in 50 years? 100 years? 150 years? How about over three hundred years from now?

How would you feel if you could go a couple centuries into the future and find something of yours - something that was very special to you back in the day - displayed in a museum with your name and a couple of sentences about the object on a placard?

You'd feel pretty special, wouldn't you?

Do you think that anything you own in your house will still be around in 50 years? 100 years? 150 years? How about over three hundred years from now?

How would you feel if you could go a couple centuries into the future and find something of yours - something that was very special to you back in the day - displayed in a museum with your name and a couple of sentences about the object on a placard?

You'd feel pretty special, wouldn't you?

I hope you have raised your children to think on the specialness of their own family and of their family history. I cannot stress this importance.

In fact, recently, I gave my other son a treasured item of mine: my Gibson J-200 acoustic guitar.

|

| The special Gibson J-200 |

I purchased this in the early 1990s and, since I don't play the guitar very much anymore, and since my son does, it was only a natural thing to do to give it to him. And give it to him now while I can enjoy him enjoying it. He deserves to have it and the guitar deserves to be played.

And do you want to know what he wrote on his Facebook page about it?

"Arguably the best sounding acoustic guitar ever made- Gibson J200

"Arguably the best sounding acoustic guitar ever made- Gibson J200

George Harrison, Jimmy Page, Emmy Lou Harris, Ricky Skaggs, and so many others have sworn by this instrument for its unmatched sound and playability. If you listen to songs like “Babe, I’m gonna leave you”, you can hear this perfect creation in action.

My dad spent years paying this off before I was born, and a year after I was, it came in. Ordered it through Joe Pistorio at Joe’s Music Quarters, the only music store I’ve ever trusted - and since then, this guitar has been the symbol of my childhood. Countless nights around the fire at the cottage. My dad teaching me to play - I remember learning “I should have known better” by the Beatles as my first song, learning “Day Tripper” with him (that’s what taught me bar chords).

The smell of this guitar and the case it comes in brings all of it back.

My dad has told me for years that this would one day be mine.

Today he surprised me with it and it’s overwhelming.

I changed the strings and it’s every bit as good as I remembered.

There aren’t words to express how important this is to me.

Tonight didn’t permit me to record like I hoped to, but I’m so grateful today. Even if on Monday my job frustrates me, my kids are screaming about how even though my food is delicious they don’t want it, and the dog keeps uncovering my fig tree, I won’t care. This means everything."

January 6, 2024

Believe me, I have other items for my other kids...some of which, again, they have in their possession.

|

| The desk my mother bought for me for Christmas in 1982. Simple, yet filled with quality. You can see the nicks and scratches from my use of it. Every nick and every scratch has a story to tell...a story as I wrote stories...and as I did music and history research. Another son of ours now has possession of this, for he is the one who uses it the most. And, who knows? One day this may belong to one of my grandkids, should my son decide not to have any children of his own. |

|

| A Christmas gift - my daughter's grandparents kitchen table. All restored. |

We were blessed to have my mother live with us for many years. And in that time she would regale my children with stories of her younger days: about riding in a rumble seat, growing up during the Great Depression, her home front World War Two experiences, meeting my WWII soldier father and then marrying him.

And of their first kitchen table they bought together, around 1950-ish.

After my mother had passed away in 2017, we still had that very same table in our home. Sadly, the wood dried and cracked and literally began to split. Lucky for me, I have a wood-working friend who knows how to do restoration, so he restored this wonderful piece of our family history.

We gave the table to my daughter as a Christmas gift in 2022 - well...the table was not the actual gift, but the idea that we had it restored was.

She loved it!

Paying tribute to family, and keeping & caring for family heirlooms honors ancestors as very little else can.

When you visit a museum, especially one like The Henry Ford where items of everyday life are prominent, remember that nearly everything you see has a history of its own. It's not just an old wooden trunk or desk or chair you see displayed, but an item that probably had great meaning to the owner(s), which is the reason why the object still exists.

I also hope that I gave you a different perspective on your own items in your home: furniture, magazines, a diary/journal, precious dinnerware, collectibles like Department 56 houses...anything of quality and can last lifetimes to build memories are worth passing on as heirlooms.

|

| ~Clock from circa 1890s to about 1900~ This clock belonged to my grandfather. I believe it was given to him when he retired from the Detroit Stove Works back in 1958. Grandpa hung it on the kitchen wall at our family cottage, and that's where it stayed, even after he died in 1972, until around 1999 when I asked my family if I could have it for the "Greenfield Village room" in our house. There's not one of my grandfather's grandchildren who doesn't remember falling asleep to its tic-toc as the pendulum swung back and forth. Lots of memories with this clock. |

|

| ~Singer sewing machine made in 1918/19~ My grandfather gave this to grandma as a wedding gift in 1920. I vaguely remember seeing her sewing when this sat at the cottage (the same cottage as the clock), but my imagination now wanders back to the 1920s, 30s, and 40s when she sewed for her husband and two sons. |

We keep hearing that the younger generation will not/does not want our things. Those who feel they know better keep pushing this narrative - brainwashing, I call it - to where this thought process is actually coming true. People are getting rid of their treasures because silly psychologists in "The Atlantic" magazine and New York Times newspaper are all telling us to "declutter" our homes.

Well, I'm not.

I believe that kind of thinking is a load of crap.

I believe we should teach our children and grandchildren the importance of family, of family heirlooms, and of the memories associated with it all.

To think of the respect and the honor given to Hannah Barnard by her descendants is about as touching as anything can be; naming a granddaughter, a great granddaughter, and a great great granddaughter after Hannah can only be described as a testimonial to family in the truest sense. I've tried to do it with my own children: Each of my four offspring have family names. Of this I am proud.Paying tribute to family, and keeping & caring for family heirlooms honors ancestors as very little else can.

When you visit a museum, especially one like The Henry Ford where items of everyday life are prominent, remember that nearly everything you see has a history of its own. It's not just an old wooden trunk or desk or chair you see displayed, but an item that probably had great meaning to the owner(s), which is the reason why the object still exists.

I also hope that I gave you a different perspective on your own items in your home: furniture, magazines, a diary/journal, precious dinnerware, collectibles like Department 56 houses...anything of quality and can last lifetimes to build memories are worth passing on as heirlooms.

~~~~~~~~

All of the information herein came from The Henry Ford Museum and from the book, The Age of Homespun by Laurel Thatcher Ulrich (in which an entire chapter is dedicated to Hannah Barnard, the Barnard family, as well as the court cupboard).

~ ~ ~