A spring sunrise over the 1750 Daggett House, a colonial living history meeting to prepare for the upcoming reenacting year, an old miniature stage coach, a visit to the Henry Ford Museum turns into a very quick Greenfield Village presentation, a few "new" Bicentennial collectibles, and...I am in print!

There---that's your table of contents for today's post. I do hope you enjoy it - I tried to keep it (mostly) upbeat and light-hearted.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

If it's March in Michigan, it means it's Maple Syruping season!

And we covered that

HERE.

|

| Spring blooms at Greenfield Village |

But it's also the time for spring! So let's celebrate!!

By the way, did you know there are two springs...sort of?

First off, we know that the astronomical seasons are:

Spring Equinox: March 20 (and it will be that date until the 22nd century)

Summer Solstice: Around June 21

Autumnal Equinox: Around September 22

Winter Solstice: Around December 21

But did you know that we have meteorological seasons, which allow meteorologists and climatologists to break the seasons up into four groups of three months based on the annual temperature cycle, as well as the calendar? The meteorological seasons do not change or vary by year. Those seasons are:

Spring: March 1 to May 31

Summer: June 1 to August 31

Autumn: September 1 to November 30

Winter: December 1 to February 28 (or February 29 during a leap year)

To be honest, this is (mostly) the way I think of our seasons, though I have to admit I do get excited on the vernal equinox (the "official" first day of spring).

Just thought some might be interested in this bit of a fun-fact~

My friend, Tom, who works at Greenfield Village, took some amazing 1st day of spring sunrise pictures that just happened to include my favorite house (hmmm?).

"But Ken," you say, "I thought you were a winter person!"

I am...in the winter.

In spring I am a spring person, summer a (mostly) summer person (except for those extreme hot & muggy/humid days), and, especially in autumn I am an autumn person. Well...I'm sort of an autumn person all year I suppose...

But today I am a spring person and celebrate the season of rebirth!

So I mentioned to Tom how much I'd love to have a few sunrise Daggett photos on spring.

He didn't disappoint!

And I have a little story to help to bring it all alive:

The sun rises on spring…

|

| Was all this going on while Tom took the pictures? |

Asenath Daggett awoke, startled. Had she overslept and not heeded her father's call? She jumped out of bed on to the strip of rag carpet laid on the cold floor. The sun was just rising and a cool, northwest breeze was blowing on this early spring morning. The well-sweep creaked in the breeze, and a whiff of the smoke of the kitchen fire, pouring out of the chimney, blew up the stairway.

In the kitchen, a glowing bed of red-hot coals burned on the hearth, streaks of sunlight glanced through the windows, bouncing off the light snow that had fallen overnight and touched the course cloth on the dinner table. Soft reflections shone from the porringers hanging on the dresser; a sunbeam flecked with bright light the brass candlesticks which were set on the mantel over the hearth.

All winter the family – her father Samuel, mother Anna, sister Talitha, and brother Isaiah - had gathered in the kitchen and, in its warm coziness, Asenath had spun on the spinning wheel, darned mittens, and knitted stockings. Being in the kitchen was a reminder of that cozy time. But with an air of spring about, the great hall was opened up once again.

Springtime truly is the season of rebirth, and thoughts for the majority of the populace in 18th century America was the need to accomplish a successful growing season, for in those long ago days, Spring was considered a time for preparing for the rest of the year; a time for a new beginning. A time for leaving the winter darkness and cold behind to look toward sunny warmth and renewal...rebirth. It would set the pace for the rest of the year.

So, being that it is now March - very early in the spring (the 1st day as I write this) - and we can still see the last remnants of the winter snows melting, this would be the time of year when the colonial farmer might’ve been repairing his farm tools to work his fields for plowing and planting. And for finding ways to make extra money -

Just imagine if the walls in this 1750 home of the Daggett family could talk…think of the daily life - the everyday activities that occurred here...the conversations spoken, perhaps very similar to what was written above---then again, perhaps these wall do talk…we only have to listen.

So hear now Samuel Daggett’s own words as you read from his ledger placed beneath the following few photos:

|

March 3, 1757 - Jacob Sherwine, debtor, for ceeping of seven cattel 5 weeks and three days: 1 three year old 4 two year olds 2 one year old more to one booshil (bushel) of ots (oats): allso for my oxen one day to plow more to my oxen to plow one day and more to my oxen to plow two days more to my oxen to dray* apels (apples) half a day |

*A dray is a low, strong cart without fixed sides, for carrying heavy loads.

............................

Springtime is the time of year when those of us who don period clothing and reenact a time long ago begin to prepare for the upcoming season of historical reenactments. And we do this in a myriad of ways.

|

| Hmmm...which house is Ken's...? |

I try to have an annual March meeting with members of Citizens of the American Colonies living history group. It was back in 2015 when I began this organization, and, so far these eight years since, it's been a pretty good success. However, to look at us you may think, "Wow, Ken, there aren't very many members."

But that's okay. It's quality I want, not necessarily quantity. That's most important to me. And though we may not be picture-perfect, each of us are working toward that goal, though we'll never be perfect...not unless we actually lived at that time, and even then some stitch-counters might still question us - lol - true! A friend of mine was doing a military timeline a few years ago, and he wore his government-issued US uniform from when he was drafted in 1968/69 to go to Vietnam. Some young punk kid, who claimed to be a historian with a college degree, argued with him that his uniform wasn't correct: the colors/dyelot was off, the buttons were wrong...and so on. My friend explained it was what he was issued when he was drafted and what he wore while serving his country. "It couldn't be!" the kid replied. They went back and forth for a bit until finally my friend pretty much told the punk to "bugger off" and walked away.

|

Yep! I don't care if you have a college education or not.

|

This can be infuriating.

Having discussions are wonderful, and everyone can learn from them. But we have seemed to lose the art of listening...and retention.

As for the punk kid, well, there was a time when one respected their elders, listened to their stories, and learned.

Ha! Not so much anymore, it seems.

So...back to our Citizens of the American Colonies meeting:

|

| The good folk that came to the meeting. |

Improving our look in accuracy is part of what I spoke on at our 2023 meeting: upping our game. "Good enough" only works for a short while. When I see some of these wonderful units back east and how well they look, why, that only makes me want to push myself harder, and hopefully that attitude will spread. Member Jackie consistently posts photos from an organization known as The Boston Garrison, and I'm glad she does, for they are a wonderful living history group out of Boston known for their top-notch quality - a group to emulate. Now, I've never reenacted with them before so I can only go by looks alone, so I would imagine with all they put into their outward appearance that they also are well-versed in the era they are representing - roughly the same time-period as Citizens of the American Colonies. And, yes, it sure does help that they are from the east coast! I hope to one day meet up with them - there is a good possibility I may to get to Massachusetts within the next year or two for a history tour, and you can bet I'll have my period clothing! So who knows?

|

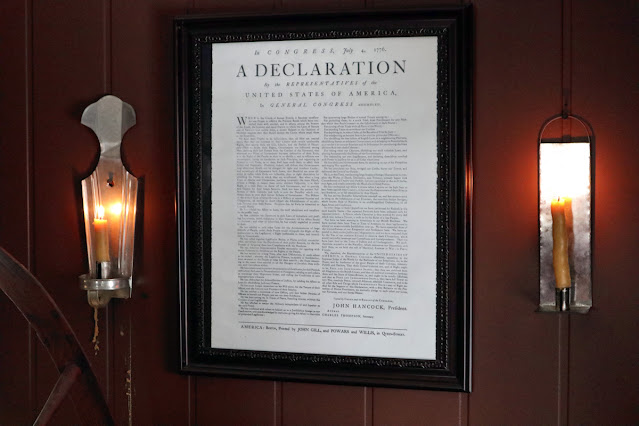

| In my own home I'm surrounded by the past... |

And, yes, I absolutely believe that surrounding yourself with period-correct accessories and learning about the times, the people, and the lifestyles of the era is every bit as important as having perfect clothing, for both you and the spectator. Think about what you are wearing as compared to how you are portraying yourself. Are you wearing fancy clothing? Then don't claim to be a working farmer or farmer's wife (for an example). Oftentimes we see perfectly dressed folk with only that - the clothes on their back and little to see and little else to bring the visitor back in time. And, too often, little knowledge about the time being represented.

..................................

|

The Lexington General Store~

It was on the wall to the right where the stage coach

sat for so long. |

Years ago…like around 40 of them - when Patty and I were still just dating, we used to visit, quite often, the General Store in Lexington, Michigan. What's cool about Lexington is that it was renamed Lexington around 1845, reportedly in honor of Lexington, Massachusetts. According to material I found on line, the general store was built in 1849 and was initially a drug store that also carried paints, oils, cigars and fancy groceries. Not long after it became a boot shop, and then other various businesses. I'm not exactly sure when it became "The General Store," but I was told it was sometime in the mid-20th century. I cannot document this, however.

When Patty and I frequented the store in the early 1980s there were two v-e-r-y nice elderly ladies that ran the place, and we would talk with them all the time. Back behind the counter was this old (even then it was old) wooden stage coach. Being ever the history buff, I would ask if it was for sale, and they always replied that it wasn’t. It kind of became a game – every time we’d go to the General Store, I would ask, “so, ready to sell that stage coach yet?” And they always smiled and said, “no, but if we do, we’ll sell it to you!”

One day…probably sometime in the late 1980s, Patty and I went in to the store, and I didn’t even get a chance to ask my question when one of the ladies quickly moved up to me and asked, “Are you still interested in that stage coach?”

I asked if she was kidding. She assured me she wasn’t, that they were selling their business and that they felt I deserved the stage coach.

I asked about the cost, and she told me. The price quoted was reasonable, but I actually probably would have paid nearly any price, that’s how badly I wanted it. I gave her the cash, she gave me the stage coach, and now it sits proudly in my living room, to this day, all these years later.

Because of this story plus my old General Store memories, it is, to me, priceless. And I will be forever thankful to those two wonderful ladies for thinking of me.

|

| There's a story to be told about this old Stage Coach... |

I'm not sure the original purpose of this old coach - was it a toy? Hmmm...seems a bit too fragile for that. No matter, for I am very pleased that it's been a treasure for me, and I hope my kids will care for it like I do when I'm gone and not just sell it at a garage sale or something.

.....................................

Just about a week before publishing this post, we had a school field trip with the high schoolers I help to teach, and went to the Henry Ford Museum. This smaller version of the Smithsonian is adjacent to Greenfield Village, the open-air museum, which is closed until mid-April. As we drove down Village Road from Southfield Freeway, we could see the tops of numerous building inside the Village walls. A number of the historic structures behind the brick wall could be seen fairly well since we were sitting high in the bus.

|

Yep - - the wall block much!

(thanks, Loretta Tester, for the photo use!) |

All of a sudden I realized that many of these kids had never been to Greenfield Village before - and neither did a couple of the adults - so I got excited, put on my pretend presenter cap, and, though I've never worked for the Village, I know how to present and I know virtually every building that sits inside those brick walls.

And as we drove past I began pointing and making quick comments (for the bus was doing the 30 mph speed limit). The pictures here, by the way, were taken from over-the-wall, but at another time. My handy dandy camera was not ready for me to take pictures while I was speed-talking.

Here's what I said:

|

...this dark gray house is my favorite, the Daggett House from around 1750,

next to that is the Farris Windmill from 1633... |

|

...and then we have the red Plympton House from the early 1700s, and back there

in the distance is the stone Cotswold Cottage & Forge from about 1620... |

|

| ...and here is the Susquehanna Plantation built in the 1830s... |

|

...and there is the Giddings House in the way back from about 1750,

and there is the Noah Webster House from 1822 next to it on the left - he wrote

his first dictionary in that house... |

|

| ...and then we have the Ackley Covered Bridge from about 1831... |

|

...here is one of the 1st houses lit with electricity by Edison himself,

the Sarah Jordan Boarding House, and there's Edison's Menlo Park Laboratory... |

(catch my breath)

|

...and next is the brick building where the Wright Brothers built the 1st true airplane -

no, not that one in the distance---that's the Heinz House---the one directly left... |

...and that white house is where Henry Ford was born in 1863..."

Whew! All that in about a minute (or less)!

Obviously there wasn't time for more than what I said but it got everyone excited for when we come visit Greenfield Village this May! Can't wait!!

............................

|

Notice the red, white, and blue!

This can gave a history of Detroit's Faygo. |

For my 4th of July post in 2022,

I wrote about America's Bicentennial that took place in 1976 and how we as a country all celebrated that momentous occasion. In the post I included something like close to 90 pictures, many items from my own collection that I saved for all those many years, and lots that I found throughout the internet. Well, since that time I re-caught the Bicentennial bug and began to recollect many of the cool things I used to have but got rid of over the years. Then there are the items I remember from all those years ago but never thought to hold on to. And then there were those things that were just a bit too much money for this 15 year old boy so, though I may have wanted them, they were simply too far out of my reach. And finally, I saw things on line that I never saw or knew about back in 1976 that are just so cool---perhaps they were from out of state---and now, well, I have a few.

So, I thought I would share some of what I recently acquired with you.

Let's begin with something I remember and had in my teenaged hands, but tossed away.

In fact, they were made right here in Detroit:

Faygo celebrates the Bicentennial!

A quick history: In 1907, Ben and Perry Feigenson started bottling lager beer, mineral water and soda water. Recent Russian immigrants to Detroit, the brothers were trained as bakers. While packaging their soda water, they began playing around with the idea of creating soft drinks based on their frosting flavors.

The brothers formed the Feigenson Brothers Bottling Works, and in 1920 changed the name to Feigenson Brothers Company. In a clever marketing move, “Faygo” was adopted as the brand name in 1921 since Feigenson didn't fit on the labels very well.. They moved their growing bottle works to Gratiot Avenue in 1935, where Faygo pop is still created today.

And Faygo joined in on the Bicentennial celebrations as well by printing the founders on the label that included a sketched likeness and short biography.

|

Patrick Henry -

"Give me liberty or give me death!" -

was on Rock & Rye.

|

|

Daniel Boone - explorer of the

American wilderness -

was on the Orange Soda. |

|

John Paul Jones - naval hero -

was on Grape Soda.

|

Now here's where things get a little interesting, especially considering this was 1976:

|

Crispus Attucks,

the African-American who was

shot at the Boston Massacre,

was on Cola! |

|

and...

Lydia Darragh, a female spy,

was on Cola! |

There you have my Faygo Bicentennial can collection.

Others who were saluted by Faygo in this manner back in the 1970s were:

Pocahontas - Jamestown ---- saved Captain John Smith's life

Nathan Hale - one of Washington's spies

Molly Pitcher - saluted Mary McCauley, who fought at Battle of Monmuth

Peter Salem - black minuteman who fought at Bumker (Breed's) Hill

Francis Marion - "the old swamp fox"

Johnny Appleseed - planted apple seeds

Haym Solomon - liberty-advocating spy

Casimir Pulaski - fought at Brandywine and other battles

George Rogers Clark - organized a northwest militia

T. Kosciuszko - traveled from Poland to fight for American Independence

Israel Putnam - popular soldier known as "Old Put"

I think what I like is that they did not have just "the hits" - the most famous of "founding" names - but included many of the "bubbling unders" as well - some of who are not as well known but still gave much to the cause - which I think is very cool, especially given the time these were printed.

Other "cool"ectables I found include picture-postcards that were collected but never sent:

|

| There are more in the collection, but I liked these the best. |

I bought this in collection form off eBay. I paid more than I would've liked but, well, at least I have them.

It seemed like every single company that produced anything got into the Patriotic spirit!

|

Oh man! I would've loved to've had these notebooks for school!

Yep---they're all from 1976!

And I did purchase them...too late to use for class

(not that I would - they're just too cool) |

Also part of the 200th celebration:

I remember begging my parents to take me to Greenfield Village to witness the Bicentennial celebrations going on there. After reading of the activities advertised in the papers, it was something I desperately wanted - no...absolutely needed - to see!

Unfortunately, it was not to be.

However, very recently I did find a copy of their trifold they handed out to the visitors who were able to go:

|

Because I so desperately wanted to go but couldn't,

this trifold listing of events is the next best thing,

for I can now see what I missed (lol).

If I could turn back the hands of time... |

And below here is a portion of what's inside the folds:

|

Between the Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village, it was a buffet of

only the finest for the history buff and Bicentennial celebrator.

Sing with me again: "If I could turn back the hands of time..."

(thanks to Tyrone Davis for such a great song!) |

I continue to seek out Bicentennial items, but not just any old thing with the Bicentennial emblem---there are certain collectibles that I am interested in, just not everything. Even I don't always know what I necessarily want until I happen to see it, and it'll reach out and grab me. You see, I don't collect to resell, I collect because I like and want the item.

That's it in a nutshell.

.

And, finally, here is something I am pretty proud of:

|

| Recently I received this very large magazine in the mail... |

I'm not familiar with this magazine, but as I began to skim through it, my mouth dropped, for it was filled with beautiful color photographs - hundreds of them! - of, as the title states. historic homes...mostly from the colonial period!

|

| Here is a sample page of what's inside~ |

Well, I wondered how and why did I receive such a gloriously thick dream book?

Then I remembered:

not too long ago, the publisher emailed me to ask if they could use a portion of something I wrote about spring and the New Year (from

THIS post), and I approved and asked it I could get a copy of the magazine once published.

Well, this is it!

Wow!

|

| My article, of which I am so proud to have in print~ |

|

And there is my name!

|

And near the back of the magazine is the information for Passion for the Past!

I enjoy the fact that in a small way I can be associated with American history.

Check it out for yourself

HERE

.....................................

You may have noticed that I said nothing about going to the Kalamazoo Living History Show, something I very rarely miss. Well, unfortunately, for the few of us who planned to ride together we had the perfect storm occur right on that very weekend: I got a super nasty cold which just about knocked me out, two others in our ride-a-long group had personal situations that prevented them from going as well, and then there was a nasty snow squall that was so bad it caused a 50 car pile up and about another 100 near misses, shutting down one of the freeways for neatly seven hours.

I suppose that it just wasn't in the cards for this year.

sigh

I certainly hope the rest of the year's events don't have similar situations.

Thank you for stopping by. Forward into the past we go!

Until next time, see you in time.

To check out my posting about the Bicentennial, click

HERETo read about springtime visits to Greenfield Village, click

HERETo read a more in depth article about the Daggett House, click

HERE

~ ~ ~