Don't you just love how an idea will just *pop* into your head, and then something you are simply

"okay with" all of a sudden becomes exciting?

That is exactly how I feel about today's posting. I've written about Samuel Daggett and his family (and house) numerous times before, but not quite in this manner; I believe this is as close as one can come to sort of meeting the man who once lived in that wonderful house with the long-slanted roof at the far-end of Greenfield Village. It is my hope that after reading this, visitors to the Daggett House will see it with new eyes...with an engulfing awareness, and will look at this historic 18th century building with a more discerning and intimate mindset; to see beyond the walls and presenters and feel the spirits - not ghosts, mind you - of those who once lived within the walls during the time of the good old colony days.

Ahhh...if only walls could talk indeed!

And yet, they do.

......................

Well, I decided to do the same project again, though with another historic house inside the Village, the Daggett Farmhouse, built around 1750.

Though it took me nearly two years to get them all, seeing the seasonal changes over the course of a calendar year is, to me, quite interesting. But it became so much more...for this post I did something a little different than the Firestone post: not only did I include a bit of historical seasonal information beneath each picture, I also included notations taken from the actual account book of Samuel Daggett himself, which you will see italicized beneath each photo.

January

February

March

April

May

June

July

August

September

Something that is not expressed nearly enough in the life of the Daggett Family is their religious beliefs and practices. They were staunch Congregationalists, and, thus, were a direct descendant of the Puritan practices of a century earlier. Sam Daggett was a Deacon in his local church (the First Congregational Church of Andover is what it is known as today), as was his father, John Daggett, and his son, Isiah Daggett. Simply put, the main task of the Deacon was to assist the Minister in leading the church. Different Churches will have their own tradition or agreement about what duties should be carried out.

October

November

There are a few undated notes that Daggett left in his account book where he cites various other jobs:

They celebrated the coming of spring and of the harvest time. They enjoyed church picnics and weddings, and certainly mourned when loved ones, whether friends or family, had passed away - I wonder how Samuel felt making coffins for those in his community, for those he knew?

Now, when reading the accounts of Samuel Daggett, pay close attention, for all the extra labor he was involved in was quite varied. And it gives us a good idea as to some of the activities that went on in and around this home and his community during the period from about 1750 to the 1770s. I think you'll agree after reading them that Mr. Daggett was an amazing man. I mean, with all of the extra work he did, when did he have time to farm, much less eat and sleep?

The spelling is mostly as it originally appears in his own write, by the way, lest you think I am a poor speller myself (lol).

So first let's take a peak into the life - the background - of Samuel Daggett by looking into his background and the environment in which he lived:

So first let's take a peak into the life - the background - of Samuel Daggett by looking into his background and the environment in which he lived:

|

| The sun rises on another day in the 18th century (this wonderful photo was taken as a favor to me by Tom Kemper) |

Daggett built this particular house in Coventry (now Andover), Connecticut around the year 1750, right about the time he married his wife, Anna Bushnell. Samuel and Anna had three children: daughters Asenath (b. 1755) and Talitha Ann, born 1757, and a son, Isaiah, who was the youngest and was born in 1759.

Daggett was a housewright by trade and built his home on a spot known as Shoddy Mill Road, atop 80 acres of land, half of which had been deeded to him by his father. Samuel also framed nearly every other house and barn in the surrounding area, as his account book at the Connecticut Historical Society attests. In order to provide for his family, Daggett had his hand in additional sources of income, including making furniture such as chairs, making coffins, as well as making and repairing spinning wheels and even cart wheels.

The use of living spaces in the Daggett house represents a sort of transitional period that incorporates both earlier modes of living, where room functions overlapped and there was little concept of personal privacy, to a move toward greater room specialization and a growing appreciation for privacy.

Note the following photos and descriptions of functions for each room to have a better idea of the living situation inside the walls of this 270+ year old home.

Let's head to the Daggett 2nd floor - - - - - - - -

|

| Here I am, heading up the spiral stairs. It is a rarity to be able to visit the 2nd floor, and I was privileged to be able to do so while in my period clothing. |

|

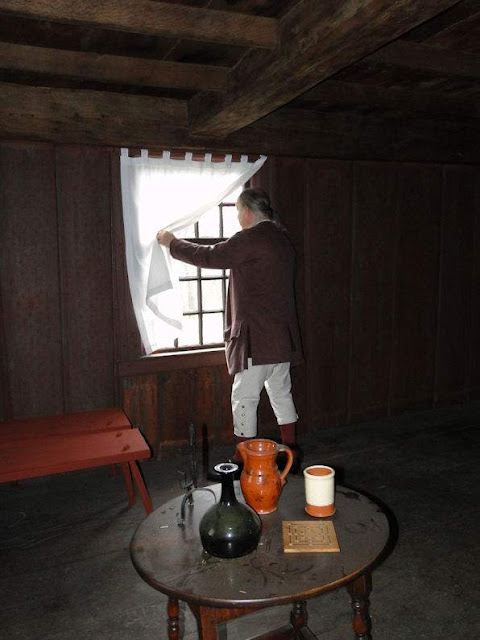

| Looking out the top front window. |

|

| Heading back "below stairs," as they say in Colonial Williamsburg. |

|

| Going down... Greenfield Village no longer allows visitors to see such spots. I am very glad I was able to do so at a number of the dwellings there. |

By the mid-18th century, even common homes came to be filled with objects of usefulness and display, in number, in kind, and in variety previously reserved only for the very well-to-do. The typical dwelling of 1750 had three times as many furnishings of a house with owners of the same social status from 100 years before. It is assumed the Daggetts were no different.

It also should be understood that no farm could be called self-sufficient---all, at some time during the year, had to call on the outside world for material goods of one sort or another.

The Daggett house would have been furnished according to room use as described in the photos above, and included would have been Anna's "marriage portion," which would have consisted of furniture, domestic textiles, domestic equipment (pots, pans, and other cooking utensils, among them), and possibly tableware like ceramic and glass that Anna's parents would have given to her when she and Samuel married. These would have been purchased by her parents or taken from their own furnishings.

Then there were the additional furnishings made by her husband Samuel. From the account book we know that he made chairs, chests, bedsteads, and spinning wheels. Because of this we can assume that he was also handy at fashioning smaller wooden items such as storage boxes and kitchen utensils.

Other necessary commodities (like wrought iron and perhaps leathered goods, coopered items, redware, pewter, hardware, cast iron, and pewter) would have been produced by local artisans.

Besides the locally made products, farmers might travel on horseback to the nearest market town to make small purchases as needed for themselves and perhaps for others/neighbors to bring back.

|

| Coventry, Connecticut landowners at the time of Samuel Daggett |

Occasionally, peddlers with small-wheeled carts would exchange needed products for farm produce or even ashes that could be made into potash for soap.

So let's visit Coventry, where the Daggett's lived, to help give us a clearer look at Daggett's environment:

(click the picture to the left to get a better idea of Samuel & Anna's community)----in laying out the town of Coventry, the traditional Puritan plan of settlement (with village green, commercial center, small home lots, and common land) was abandoned in favor of large, individual farm lots scattered across the countryside (78 in all). But people were far from isolated. They felt a strong sense of community, cemented by networks of trade, by frequent visits between neighbors, and by the ways neighbors helped each other out.

Coventry, like other scattered farm communities, did not have a town center, but it did contain artisans (Daggett, of course, was one), mills, and probably one or more retail shops (possibly out of a farmer's home). Taverns, in addition to feeding and housing travelers, were important social centers for local men to converse about politics, trade, and agriculture. In 1774, Coventry had no less than seven taverns! But one must remember: taverns were the pulse of 18th century life, and their importance to the local community cannot be overstated, for with most communication being by word of mouth, they were also the main source of information for the locals.

|

| Aside from the house itself, to my knowledge there are no actual samples of Samuel Daggett's wood work known to still exist, so the furnishings you see in these photos are well-researched similar examples, and we can assume their design would have been familiar to Samuel & Anna. |

Oftentimes we hear from the presenters inside the Daggett home that he and his family were Congregationalists in their religious beliefs. However, what is a Congregationalist in comparison to a Presbyterian, Methodist, or even Catholic?

Congregationalism in the United States consisted of Protestant churches that had a congregational form of church government and trace their origins mainly to Puritan settlers of colonial New England. Their churches have had an important impact on the religious, political, and cultural history of the United States, for their practices concerning church governance influenced the early development of democratic institutions in New England. Congregationalists were also known for their interest in an educated clergy. For that reason they founded Harvard College. Later, colleges such as Dartmouth, Olivet, and Oberlin were organized by their efforts.

The American Congregational community was a part of the Great Awakening, a widespread religious revival movement that began in 1734 under the influence of Jonathan Edwards. The Awakening, however, revealed the differences emerging between two wings of Congregationalism. On one side were those who maintained the Calvinist tradition with a greater emphasis on the affective elements in religion. On the other was a rapidly growing Unitarianism, which paralleled a similar movement in England. With the exception of the churches in Connecticut (the colony in which the Daggetts lived) where Congregationalism had taken root and remained the established church from the 18th century into the 19th century.

Congregationalism is a direct descendant of Puritanism, and Puritans were part of a strict religious movement in early American history that emphasized strict moral discipline and purity as the correct way to live as a Christian. Puritans believed that if they honored God, their colony would be blessed, and if they failed to, it would be punished. This led to strict laws, including mandatory church attendance.

It is interesting to learn that during the American Revolution, most Congregational ministers sided with the Patriots and American independence. This was largely because ministers chose to stand with their congregations who felt the British government was becoming tyrannical. Ministers were also motivated by fear that the British would appoint Anglican bishops for the American colonies. This had been proposed as a practical measure; American bishops could ordain Anglican priests in the colonies without requiring candidates for ordination to travel to England. Congregationalists, however, remembered how their Puritan ancestors were oppressed by bishops in England and had no desire to see the same system in America.

In the 18th century, Congregationalists in New England lived lives deeply intertwined with their church community, prioritizing strict moral conduct, regular church attendance, education, and active participation in local governance, where church membership often correlated with the right to vote; their daily lives were heavily influenced by Puritan values, with a focus on hard work, family life, and living according to biblical principles, while also engaging in community activities like town meetings held within the church building itself.

This is what the Congregationalists, such as the Daggett family, are directly descended from and strongly believed. In fact, Sam's father, John, was a Deacon in his church - a very important position - as was his Sam's own son, Isaiah. However, I learned through research and former presenters that it seems at one point later in his life, though not sure when exactly, Sam left the Congregational church and joined the local Baptist Society of Coventry.

Why?

I cannot say for certain, for the beliefs and ties to Puritanism from both denominations were very closely related. As I learned through my research:

"The Baptist Society of Coventry, Connecticut, while sharing some similarities with Congregationalists due to their Calvinistic roots and early presence in New England, eventually developed distinct practices and beliefs. Both denominations stemmed from Puritanism, but the Baptists emphasized believer's baptism (baptism of adults who profess faith) rather than infant baptism, a key point of divergence."

So that could be our answer; perhaps Samuel questioned the tenets or authority of this church. I was also told this may have caused some possible tension between he and Isaiah.

Either way, the Daggetts were very involved in their repective churches. I have little doubt that Anna and maybe the girls might have followed the man of the house, though as of this time I have no proof.

|

It looks like Sam left his Bible on the table. Oh, but Asenath also does her school reading studies by using this family heirloom. This is a replicated 1733 New Testament Bible (check out this site Bibleman run by James Moore) |

We are also told that Congregationalists and Baptists of that time did not generally celebrate Christmas. However, did they celebrate Easter or any other holidays/holy days? I have found nothing either way on whether or not the Daggetts celebrated Easter, though from what I have read, most of their denominations may not have. They viewed it much in the same manner as they viewed Christmas, thus the Holiday being another Papist (Catholic) Holiday, of which they despised, and the date not being biblically based.

|

| I see Anna, Asenath, and Samuel... but where is Talitha and Isaiah? |

I do wonder if this family celebrated the other seasonal holidays of the period, such as Candlemas (doubtful), Rogation Sunday (strong possibility), and Lammas Day (50-50).

However, I have little doubt, as my religious research shows, that they did celebrate Thanksgiving/harvest time, in which giving thanks for a bountiful harvest IS in the bible (Exodus 23.16: And the feast of harvest, the firstfruits of thy labours, which thou hast sown in the field: and the feast of ingathering, which is in the end of the year, when thou hast gathered in thy labours out of the field), and thanked God for their bounty received. Though there were days set aside for Thanksgivings throughout the year, the 17th and 18th centuries New England colonies celebrated HARVEST Thanksgivings on various days, and these days were often held in late November to mark the end of the agricultural year. Early on, these harvest Thanksgiving celebrations were largely church-based, beginning with church services and a proclamation read from the pulpit - a day set aside for prayer and fasting, not a day of feasting. That changed later in the 18th century where Thanksgiving celebrations included family reunions, recreation, and festive dinners, and food, family, & friends gatherings would occur.

Would the Daggetts have celebrated so merrily? Perhaps, though at this time I have no information either way. However, as the Daggetts were a strong Congregationalist family, I would like to include what I believe is a fitting Thanksgiving prayer here from the 18th century:

“O MOST merciful Father, who of thy gracious goodness hast heard the devout prayers of thy Church, and turned our dearth and scarcity into cheapness and plenty: We give thee humble thanks for this thy special bounty; beseeching thee to continue thy loving-kindness unto us, that our land may yield us her fruits of increase, to thy glory and our comfort; through Jesus Christ our Lord.

Amen.”

While both 18th century Congregationalists and Baptists shared some common ground as Dissenters from the Church of England - both faiths coming directly from the Puritans - their differing stances on doctrines like baptism (Baptists insisted on believer's baptism by immersion, meaning individuals must have a personal conversion experience and confess their faith before being baptized as adults, while Congregationalists generally practiced infant baptism, believing it signified membership in the covenant community and the hope for a future conversion experience) and the role of the state led to their distinct denominational identities in the 18th century.

I find it interesting that the Daggetts came from a religious belief that ties them directly to Puritans, who valued order over other social virtues, reasoning that men required rules to guide them and bind them to their good behavior. Here, authority dominated people's lives, beginning with the highest authority of God, then the authority of religious leaders, and finally the authority of the male head of the household.

We do find that by the 1760s changes were on the horizon, many of these attitudes would have still described rural New England families. They still perceived themselves as deeply religious people, and being the father, son, and grandson were greatly involved in their church shows this in the Daggett family. They observed the hand of God in everyday occurrences. They believed in order, hard work, and maintaining high moral standards.

Something as important as faith & religious beliefs are sorely missing in today's presentations, in nearly all museums that I have ever visited. A mere mention is simply not enough in helping visitors to understand lives from long ago, especially of a faith that is not as well known. Religious beliefs cannot be ignored if one wants to truly show a more accurate life of the time.

So...let's go back and visit with Samuel, Anna, and the other Daggetts...and we can begin with...

|

| Samuel Daggett: In His Own Write~ Yes, this is an actual page from Samuel's own account book. Just imagine...he wrote what you see here while living in this house that now sits inside Greenfield Village. Pretty cool, eh? |

January

|

This picture was taken soon after a mid-January snowstorm. One can just imagine... Even with the cold and snow, Samuel & Anna Daggett, with their children, kept themselves busy; Anna in the kitchen preparing and cooking a meal in the hearth while the children did their assigned chores as well. Husband, Samuel, possibly out doing odd jobs and making more money or bartering for needed goods. Once their son, Isaiah, was old enough, he, too, would have his chores, for there was plenty of wood to be chopped and stored for hearth and home, and perhaps learning his father's wood and housewright trade. 18th century life. January 20, 1750: Jacob Gill, debeter, for looking for timber for his fraim (frame) January 15, 1760: Samuel Blackman, Debtor, for mending of a foot wheel more to making of a yoak (yoke) – trimming of it January 18, 1760: wid. (widow) Sarah Loomis, debtor, to mending of a wheel January 1766: Joseph Clark, debtor, a pair of fliers to a little wheel |

|

| And here is a bright sunny February afternoon to let us know that, as assuredly as the sun will rise in the morning, springtime is nigh. Although it is still wintertime, the planning of planting the fields come springtime will take place by farmers. The dried apples from last October certainly taste good! February 6 yr. 1749: Peres Sprague, debtor, for two chears (chairs) more to making of a slead (sled) more to hanging a lithe (sythe? laithe?) more to cradeling of oats / more to bail February 23, 1750: Peres Sprague debeter for a half a booshil (bushel) of pertators (potatoes) more to a seed plow and to a whorl more to a peck of pertators and 4 pounds of tobacco more to creadling (cradling) of two akors (acres) and 1/2 of an akor more to hanging of a lithe (sythe? laithe?) and making a cain (cane) Capt Obediah Nucomb, debter, for a cart and wheels (a worl is a flywheel or pulley, as for a spindle) February 9, 1761: Abraham Blackman, debtor, for making of a spoll (spool) and fliers (flyers) to a (spinning) wheel. February 24, 1764: Ephraim Shalfer's widow, Debtor, for mending of a wheel ~(more than likely a spinning wheel) By the way, it was on February 19, 1764, that Samuel's Father, John, passed away. |

March

|

| It is now March - very early in the spring - and we can still see the last remnants of the winter snow melting. This would be the time of year when the colonial farmer might be repairing his farm tools to work his fields for plowing and planting. March 3, 1757: Jacob Sherwine, debtor, for ceeping of seven cattel 5 weeks and three days : 1 three year old 4 two year olds 2 one year old more to one booshil (bushel) of ots (oats): allso for my oxen one day to plow more to my oxen to plow one day and more to my oxen to plow two days more to my oxen to dray* apels (apples) half a day March 1, 1758: John Sherwine, debtor to flaxseed half a booshil March 11, 1760: Capt Obediah Newcomb debtor for mending of 8 chairs and a wheel. March 13, 1760: Joseph Crooker debtor for eleven booshil of heyseed at seven pence cash pr. booshil. *A dray is a low, strong cart without fixed sides, for carrying heavy loads. |

April

|

| Plowing, harrowing, and planting may also be on Sam Daggett's mind at this time, especially as the sun gradually warms the ground. Caring for the pregnant farm animals was also a top priority, for this would ensure continued generations of cattle, pigs, sheep, and horses. April was also the month that Samuel Daggett took Anna Bushnell as his bride, in 1754. According to FamilySearch, the two were wed on April 17. Aprail 7, 1749: Reverend Samuel Lockwood, debeter, for two days work hewing timber Aprail 4, 1750: more for fraiming of (Jacob Gill's) house fraim 14 days 3/4 of a day Aprail 16, 1750: Rebeckah Gibbs, debeter, to a woolen wheel Aprail 2, 1751: Mary Woodworth, debeter, to a plow more to a spindel April first (1763): more to 3 days 2 hours fraiming (of the school house) more to timber for one thousand 4 hundred and seventy of shingels / more to draining of the shingels more to 2 days of work about the school house April 25, 1767: Samuel Sprague, debtor, for 65 booshils (bushels) of hayseed 5 pence per booshil, cash price April 6, 1769: Abraham Burnap (father of Daniel Burnap, clockmaker), debtor, for work about a pair of wheels and axletree (an axletree is a bar fixed across the underpart of a wagon or carriage that has rounded ends on which the wheels revolve) April 15, 1774: Samuel House, debtor, for 4 hundred (pounds?) of hay at 2 shillings 3 pence pr hundred cash price |

May

|

| 'Tis the month of May - mid-May to be exact - and the ground is mostly prepared for planting, which can commence at any time. This was also time for washing & shearing sheep and scouring & carding wool. May 30, 1749: one day work digging of stones May 10, 1758: Daniel Nucomb, debtor, for a coffain (coffin) May 22, 1758: Credet to John Stedman in cash May 6, 1765: Benjamin Buel, Debtor, for one booshil (bushel) and two half quarts of seed corn May 11, 1765: Thomas Bishop, Debtor, for one booshil & half of rie cash price May 21, 1765: more to 7 days work framing of his (Thomas Bishop) barn more to 7 days woork of Thomas in framing more to six quarts of barly and eight --?-- of flaxseed May 5, 1770: Mary Lutchins, debtor, for one bushil of wheat and one bushil of rye more to 2 pigs, 5 weeks old and a half of a peck of corn ~(It looks like by 1770 Samuel Daggett learned how to spell "bushil" correctly!) |

June

|

This picture was taken on June 21st - the first day of summer, and that means summer's here and the time is right for caring for the farm crop and kitchen garden. And still more planting to do. June 16, 1749: Jonathan Merait, debeter, for eight days work of hewing* and framing June 21, 1749: Thomas Perceins debeter for a coffain (coffin) June 11, 1763: Nath(el) junior , Debtor, for a pair of cartwheels more to drawing of 2 tooth and mending a cartwheel more to 14 pound of veal and half 1 pney hapenny pr. pound * Hewing is to chop or hack with an axe

|

July

|

One can almost feel the heat emanating from this picture on such a hot and humid July day when it was taken. But the Daggetts were not cooling off in their air-conditioning, for obviously, they had no a/c in the 1760s! The family, instead, were very busy out doors, where any slight summer breeze would be accepted with gratitude, while doing the necessary summer duties and chores of the time. For the colonial farmer, it was usually in July that made for haying. In 18th century Connecticut, July was also a busy time for farmers and households looking to utilize the peak of summer bounty. While modern conveniences like refrigeration were absent, several fruits and vegetables were harvested and enjoyed fresh or preserved for later consumption. Fruits: blueberries, black and red raspberries, strawberries, cherries, and possibly early apples, peaches, pears, and plums towards the end of July. Vegetables: sweet corn, beans (including possibly heirloom varieties like Jacob's Cattle Bush and Early Yellow Six Week), cucumbers, bell peppers, tomatoes, summer squash (including zucchini and possibly lemon squash), beets, and cabbage. In addition to fresh consumption, food preservation played a crucial role, utilizing techniques like: Drying and dehydrating: for fruits, vegetables, and any herbs they may have. Salting and curing: especially for meats like pork, but also for butter. Pickling: vegetables such as cucumbers. Cool storage: root cellars or cool parts of the house for root vegetables, beverages, and some dairy products. This was also time for weaving wool on the loom, which would continue for pretty much the rest of the year, or until the weather was severely cold. From Sam Daggett’s own ledger book we see other means of making money: July 11 ye 1749: Thomas Wisse, debeter, for cradelings* more to cradeling two acor and 3/4 of otes July 13, 1749: Josiah Bumpus, debter, for one days work of reaping July 25, 1763: Solomon Saveary, debtor for a coffain (coffin) *The way wheat and oats were cut years ago was by 'cradeling' (cradling). Meaning he used a tool known as a grain cradle for his help in a summer harvest. All of this on top of the normal summer chores of weeding and taking care of the house and kitchen garden. Now…put that phone away and get to work! |

August

|

| Feel the heat: June 21st may be the longest stretch of daylight, but the hottest days usually take place in July & August. Even though it was August 16 when I took this picture, one can see and feel the season begin to change ever-so-slightly. Farm work continues both inside and outside the house.It was on the 17th of August in 1750 that Anna's mother, Mehetable Allen Bushnell, passed away. Samuel & Anna were not yet married. August 31, 1753: Samuel House debter to a plow August 1764: Joseph Griswold, debtor, for a coffan (coffin) for his child August 27, 1765: (added to Joseph Griswold's account) more to twelve pounds of leather more to one quarter of lamb mutton more to one calfskin tand (tanned) more to two shillings worth of leather |

September

|

| I snapped this shot on September 9, and it is easy to see the shadows of the sun grow longer. Hints of summer past and autumn future are in the air...harvest time is nigh. September 12, 1751: Sam Benet, debtor, for two days and half of work about mill and a pound of tobacco September 17, 1757: Rufus Rude, debtor, for 11 pounds of p-barke and for one pound of butter more to one pound of butter more to my oxen to draw a load of bords September 21, 1757: Elisha Bill, debtor, for two days work about his cyder mill |

Something that is not expressed nearly enough in the life of the Daggett Family is their religious beliefs and practices. They were staunch Congregationalists, and, thus, were a direct descendant of the Puritan practices of a century earlier. Sam Daggett was a Deacon in his local church (the First Congregational Church of Andover is what it is known as today), as was his father, John Daggett, and his son, Isiah Daggett. Simply put, the main task of the Deacon was to assist the Minister in leading the church. Different Churches will have their own tradition or agreement about what duties should be carried out.

So, harvest and all daily living of the Daggett family cannot be separated from their religious beliefs and practices. Showing how people of this period, like Sam Daggett and his family, actually celebrated the harvest/autumn should become priority, as far as I am concerned, for it was the most important time of year for human kind since the beginning of time. The Bible itself speaks of it multiple times:

Genesis 8:22 While the earth remaineth, seedtime and harvest, and cold and heat, and summer and winter, and day and night shall not cease.

John 4:35 Say not ye, There are yet four months, and then cometh harvest? behold, I say unto you, Lift up your eyes, and look on the fields; for they are white already to harvest.

Jeremiah 5:24 Neither say they in their heart, Let us now fear the LORD our God, that giveth rain, both the former and the latter, in his season: he reserveth unto us the appointed weeks of the harvest.

Genesis 8:22 While the earth remaineth, seedtime and harvest, and cold and heat, and summer and winter, and day and night shall not cease.

John 4:35 Say not ye, There are yet four months, and then cometh harvest? behold, I say unto you, Lift up your eyes, and look on the fields; for they are white already to harvest.

Jeremiah 5:24 Neither say they in their heart, Let us now fear the LORD our God, that giveth rain, both the former and the latter, in his season: he reserveth unto us the appointed weeks of the harvest.

And the family would have given all glory to God in whatever yield was harvested.

October

|

We are nearing the end of the month - October 22. The housewife's universe spiraled out from hearth and barnyard to tending a kitchen garden and perhaps a large vegetable garden, both now in full harvest. It was on the 6th of October in 1770 that Anna's father, Nathaniel “Nathan” Bushnell, died. October 25 ye 1748: Nathaneal House, debter, to work about his barn fraim (frame) October 1756: David Carber, debtor, for 17 yards of flaniel (flannel) at 2 shillings pr. yard more to 64 pounds of cheese at 3 shillings per pound October 1757: Joseph Crocker, debtor, 2 B (bushels) of wheat On October 23, 1767, Samuel Daggett noted in his account book that he had sold: 4 1/2 (pounds) of pork 10 quartz of cyder 15 quartz of cyder 5 quartz of cyder 2 quartz of seed corn 19 gallons of cyder by the barrel It was on October 24, 1785 that Samuel's mother, Margery Eames Daggett, passed away. |

November

|

Picture taken November 11 The falling leaves drift by the window The autumn leaves of red and gold... Since you went away the days grow long And soon I'll hear old winter's song But I miss you most of all my darling When autumn leaves start to fall (English lyrics by Johnny Mercer) Late fall harvest keeps the farm family busy, as does winter preparations.November 3 ye 1748: William Peters, debeter, to work about his cool house November 16 ye 1748: Credit to Nathanael House for making of cyder and toward other work November 23, 1749: Aaron Phelps, debtor, for work about his mill more to drawing of teeth for his wife November 25, 1749: Thomas Lymon, debter, for work about his house more to worl more to mending his cart (a worl is a flywheel or pulley, as for a spindle) November 4, 1755: Cr debtor to forty five pounds-three fourths of butter at five shillings pr pound more to four yards of plaincloath at two pounds eight shillings pr yard November 9, 1757: Beriah Loomis, debtor, 14 yards flannel cloth and half at 2 1/2 pr. Yard November 15, 1757: John Stedman, debtor for a coffain (coffin) for the making therof more for a coffain for his child more to drawing of a tooth November 30, 1762: Doc John Crocker debtor for 276 wait (weight) of porke at three pence pr pound more to going and drawing of a tooth more to three fourths of a days work more to one pound and a half of tobacco November 7, 1764: John Crocker, debtor, for one hundred and 72 pounds of poarke at 24 shillings pr hundred money price more poarke - wait (weight) of it 322 pounds - price 2 pence hapenny pr pound November 22, 1764: Joseph Griswold had two hundred and 49 pounds of beef and thirty five pounds of tallor (tallow?) more to a tap and facet and four quartz of cyder more to one booshil of ingain corn more to going and draw a tooth more to two booshils of indun corn cash price more to half a booshil of seed corn cash price more to one peck of seed corn cash price more to half a booshil of common seed corn more to five gallon of vinegar more to half a days work of oxen to draw wood more to one third part of a cord of bark |

December

| ||

The harvest, for the most part, is ended, and only a few very late vegetables await. Maybe some cabbages, brussels sprouts, lettuce, beets, potatoes, and possibly a few late carrots are all that's left to pick.

more to 2 booshils (bushels) of corn |

There are a few undated notes that Daggett left in his account book where he cites various other jobs:

I suspect this is from 1770 -

|

| Direct from Samuel Daggett's own ledger/account book in his own write (to coin a John Lennon title). And to think he wrote this while inside this very house. How cool is that? |

In the year 1763 I maid---er, made 21 barils of Cyder

in 1764 07 barils

in 1765 16 barils

in 1766 08 barils

in 1767 10 barils

in 1768 20 barils

in 1769 19 barils

By the way, it takes approximately 30 to 40 apples to yield one gallon of cider, and, depending on the size of the barrel used, about 40 gallons of cider, or slightly more, would fill an 18th century barrel.

And it would take about 60 to 65 gallons (or more, depending) to fill a hogshead.

Also listed with no dates, Samuel wrote:

Jacob Lyman, debtor, for setting a worsted comb

more to two spindils

more to four days fraiming his house

more to two spindils

John Pain, debtor, work about his fulling mill*

*A fulling mill was a water operated mill with big wooden hammers that pounded the cloth as it was being washed. Fuller's earth was used to help the cleansing process. The finished fabric was shrunken into a tighter, tougher cloth. It was similar to today's boiled wool.

......................................

I don't know about you, but to me, seeing and reading the actual words of Samuel Daggett just...I don't know...makes him real. Yes, I know Samuel and his family were actual people, but because I've heard his name and story so often - for I have visited his home so often - it almost makes him mythological...just a story to tell the story rather than a real actual human being that once lived. But he and his family did live...and had feelings the same as we do: they felt happiness, sadness, anger, pain, concern, and contentment.

|

The tombstone of Anna Daggett: Birth: 1734 Death: Jan. 28, 1832 Inscription: relict of Samuel; age 98 |

They spoke of their crops, the weather, told stories, and studied the Bible. One can only imagine the discussions and probably even debates they had of the news of the day - how wonderful it would be to be able to hear conversations and opinions about Paul Revere's famous ride (for it actually did make the papers/broadsides of the time), and the battles of Lexington & Concord that followed...and of the Revolutionary War itself, for research has shown that Mr. Daggett paid for someone named Jacob Fox to take his son Isaiah's place in military duty so that the young 17-year-old could stay home and tend the farm. This was not an uncommon practice of the day. I also see on Samuel's tombstone that it states he was a Revolutionary War veteran, though I have found nothing stating he was in the military. He did, however, play a vital citizen's role in agreeing to a formal collective decision made by the local merchants and traders not to import or export items to Britain in 1774.

|

The tombstone of Talitha Ann Daggett Carver Birth: Aug 5, 1757 Death: Aug 28, 1846 (aged 89) |

|

The tombstone of Asenath Daggett Kingsbury (and her husband) Birth: Jan 25, 1755 Death: Sept 26, 1823 (aged 68) |

I wonder of Samuel's thoughts on the Declaration of Independence, the forming of the new nation with its own Constitution, and hearing of George Washington becoming our first president as it was happening!

I mean, if the Daggett house walls had ears, they most certainly would have heard at least some talk about these great events.

One more note of interest: I have recently read that spinning wheels and the like were not used nearly as much as has been previously stated in history books.

|

The tombstone of Isaiah Daggett Birth: 1759 Death: Aug 24, 1835 (aged 75–76) |

Well, through my own research I have found just the opposite - I have seen that the omnipresence of spinning in people's lives is evidenced by the many references to spinning wheels and spinning wheel parts and repairs noted in not only Daggett's account books, but in numerous other writings, such as the journal of Martha Ballard.

And along those lines it was in Samuel's own will that he bequeathed "the loom" to his wife. It has to be assumed this was a large item for him to mention it here specifically. Though it is not known when this was acquired or used by the family, but he was selling flannel cloth, probably woven on the loom, by 1756.

See how history - how the past - can be brought to life through research?

I beg people to please stop passing along so-called historical information found on memes and the like as fact until it can be proven or have a strong researched-based probability.

Until next time, see you in time.

Postscript:

~I write often about the Daggett Home. There is simply something that pulls me to it like no other. And it always has, ever since I saw it for the first time back in 1983. And now I always make sure to stop in for a visit every time I am at Greenfield Village, even if it is just a quick walk through, from the front door through the great hall into the kitchen and out the back door into the kitchen garden. And while the Village is closed during the winter months, I will drive on the road that runs alongside the Village, just so I can see and somewhat enjoy it from my car.

~I write often about the Daggett Home. There is simply something that pulls me to it like no other. And it always has, ever since I saw it for the first time back in 1983. And now I always make sure to stop in for a visit every time I am at Greenfield Village, even if it is just a quick walk through, from the front door through the great hall into the kitchen and out the back door into the kitchen garden. And while the Village is closed during the winter months, I will drive on the road that runs alongside the Village, just so I can see and somewhat enjoy it from my car.

Winter in the Colonial Days - A Pictorial

A modern picture album of winter life 250 years ago, mostly taken at Colonial Williamsburg and Greenfield Village. And, yes, there is history to be told as well.

Hallowe'en Through the Ages

This posting shows a varied celebration of Hallowe'en, and interspersed throughout are snips and bits of Hallowe'en history and lore. The many pictures and the historical information should hopefully bring what was (and still is) a children's holiday up to the level of adults as well, for, initially, Hallowe'en was actually meant for adults.

A Colonial Harvest

It's the fall, and that means it's time to harvest your crops.

Let's take a step back in time to see how this was done in the age of the founding generation.

A Colonial Thanksgiving

Aside from what we call the 1st Thanksgiving in 1621, there is much more to the story in the formation of this most beloved American holiday.

A Colonial Christmas

Read on to learn that, contrary to popular belief, many of our colonial ancestors - from New England to the South - truly did indeed celebrate this glorious holiday ...

...and how they celebrated

Oh! Myths thought as truth can sometimes be so hard to change, even with primary sources ~ ~ ~

A Colonial New Year's

In our modern era we think of the New Year's holiday as a time for celebrators to stay up extremely late, getting stupidly drunk, watching the ball drop, and then gorging themselves on pizza, chips, and other snacks for 12 hours-plus while watching more football in one day than anyone does in an entire season.

My how times have *somewhat* changed...

In the Good Old Colony Days

A concise pictorial to everyday life in America's colonies. And I do mean "pictorial," for there are over 80 photos included, covering nearly every aspect of colonial life.

I try to touch on most major topics of the period with links to read more detailed accounts.

This just may be my very favorite of all my postings. If it isn't, it's in the top 2!

It's the Little Things

Another post that touches on a variety of subjects, such as Shadow Portraits, Bourdaloues, Revolutionary Mothers, and a few other interesting historical odds & ends.

A Year on a Colonial Farm

See what it was really like, month to month, for farm folks like Samuel Daggett and others as you spend all four seasons on an 18th century farm.

Researching 18th Century History

Here is a collection of my favorite books in my library that I use, seemingly, on a daily basis, especially when writing in this Passion for the Past blog.

Other people spend their money on sporting events and the like, I buy books.

I hope you enjoyed this seasonal excursion into the past, and I hope the writings of Samuel Daggett, along with my additional researched farm chores, helped to bring the man, his family, his community, and even, to an extent, his house to life.

If these walls could talk...they kinda do...and, in fact, I have a whole slew of Daggett presenter videos you can watch, just by copying and pasting the link here into your task bar:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kDlHc2gMwkM&list=PLi_a0lO-I6X7gLTfCt-mYJ13zuiI1WGhN&index=2

Postscript:

~I write often about the Daggett Home. There is simply something that pulls me to it like no other. And it always has, ever since I saw it for the first time back in 1983. And now I always make sure to stop in for a visit every time I am at Greenfield Village, even if it is just a quick walk through, from the front door through the great hall into the kitchen and out the back door into the kitchen garden. And while the Village is closed during the winter months, I will drive on the road that runs alongside the Village, just so I can see and somewhat enjoy it from my car.

~I write often about the Daggett Home. There is simply something that pulls me to it like no other. And it always has, ever since I saw it for the first time back in 1983. And now I always make sure to stop in for a visit every time I am at Greenfield Village, even if it is just a quick walk through, from the front door through the great hall into the kitchen and out the back door into the kitchen garden. And while the Village is closed during the winter months, I will drive on the road that runs alongside the Village, just so I can see and somewhat enjoy it from my car.The man you see to the left is about as close to seeing Samuel Daggett (without the beard, however) as we may ever get: it is a late 19th or early 20th century photograph of Samuel & Anna's great grandson, John Kingsbury (1817 - 1913) (grandchild of Asenath Daggett). John Kingsbury was 15 years old when his great-grandma Anna Daggett died, though it is hard to say if they ever met, for by the time John was born, his parents and grandparents had moved roughly about 250 miles northwest to Cazenovia, New York (near Syracuse), while great grandmother Anna remained in Andover, Connecticut.

Now sitting as pristine as it did over 250 years ago inside the walls of Greenfield Village in Dearborn, Michigan, the Daggett house, and those who once lived in it are, to me, like old friends---really old friends...and there are still stories it can tell us~

My sources for today's posting comes mainly from

~The Collections of the Henry Ford (Benson Ford Research Center)

~Our Own Snug Fireside by Jane C. Nylander

~Find-A-Grave (for the tombstone pictures and information)

~Everyday Life in Early America by David Freeman Hawke

Here is a collection of links to my blogs concerning everyday life in the colonies:

In this posting we learn more about the Daggett House itself, including its own history and how it came to be relocated to Greenfield Village, a more in-depth tour and study room by room, with virtual tour videos included as well from the presenters who work there, and even information on the kitchen garden. Sixty photos, most of which you may not have seen before.

Winter in the Colonial Days - A Pictorial

A modern picture album of winter life 250 years ago, mostly taken at Colonial Williamsburg and Greenfield Village. And, yes, there is history to be told as well.

To Drive the Cold Winter Away: ~ A collection of notations of surviving wintertime past - Colonial and Victorian~

Just how did our colonial, and even Victorian, ancestors survive in such harsh weather? How did they stay warm in below 0 degree temperatures? How did they entertain themselves on cold winter nights without radio, TV, or the internet?

This is how.

A Colonial Spring

March was the first month of the new year back in the good old colony days, and there were plenty of chores and other work that needed to be done. The whole family would pitch in to ensure survival for the coming year.

This is how how ancestors did it.

A Colonial Summer

Beating the heat, hiding from bugs, sowing and growing plants for survival, milking, pulling flax, haying, and preparing for the fall harvest.

Welcome to summer in the 1700s.

Just how did our colonial, and even Victorian, ancestors survive in such harsh weather? How did they stay warm in below 0 degree temperatures? How did they entertain themselves on cold winter nights without radio, TV, or the internet?

This is how.

A Colonial Spring

March was the first month of the new year back in the good old colony days, and there were plenty of chores and other work that needed to be done. The whole family would pitch in to ensure survival for the coming year.

This is how how ancestors did it.

A Colonial Summer

Beating the heat, hiding from bugs, sowing and growing plants for survival, milking, pulling flax, haying, and preparing for the fall harvest.

Welcome to summer in the 1700s.

Revolutionary War houses situated in our favorite open-air museum, from Daggett to Plympton to Giddings...and even bits on other colonial homes.

Hallowe'en Through the Ages

This posting shows a varied celebration of Hallowe'en, and interspersed throughout are snips and bits of Hallowe'en history and lore. The many pictures and the historical information should hopefully bring what was (and still is) a children's holiday up to the level of adults as well, for, initially, Hallowe'en was actually meant for adults.

A Colonial Harvest

It's the fall, and that means it's time to harvest your crops.

Let's take a step back in time to see how this was done in the age of the founding generation.

A Colonial Thanksgiving

Aside from what we call the 1st Thanksgiving in 1621, there is much more to the story in the formation of this most beloved American holiday.

A Colonial Christmas

Read on to learn that, contrary to popular belief, many of our colonial ancestors - from New England to the South - truly did indeed celebrate this glorious holiday ...

...and how they celebrated

Oh! Myths thought as truth can sometimes be so hard to change, even with primary sources ~ ~ ~

A Colonial New Year's

In our modern era we think of the New Year's holiday as a time for celebrators to stay up extremely late, getting stupidly drunk, watching the ball drop, and then gorging themselves on pizza, chips, and other snacks for 12 hours-plus while watching more football in one day than anyone does in an entire season.

My how times have *somewhat* changed...

Going into far greater detail than today's post, this is an overview through twelve months in the life of an 18th century farmer, giving the reader a deeper sense of a colonial farm family's seasonal life.

Travel and Taverns

The long air-conditioned (or heated) car ride. Motels without a pool! Can we stop at McDonalds? I'm hungry!

Ahhhh....modern travelers never had it so good.

I've always had a fascination of travel back in the day, and I decided to find out as much as I could about them.

I wasn't disappointed - - - I dug through my books, went to a historic research library, 'surfed the net' (does anyone say that anymore?), and asked docents who work at historic taverns questions, looking for the tiniest bits of information to help me to understand what it was like to travel and stay at a tavern in the colonial times.

This post is the culmination of all of that research.

Our country's founding relied greatly on the tavern.

Cooking on the Hearth

No stoves or fast food restaurants. Everything made from scratch.

What was it like for our colonial ancestors to prepare, cook, and eat their meals, and what kinds of food were available to them? How did they keep their foodstuffs from spoiling and rotting?

If you have questions such as this, I believe you will enjoy this post.

The long air-conditioned (or heated) car ride. Motels without a pool! Can we stop at McDonalds? I'm hungry!

Ahhhh....modern travelers never had it so good.

I've always had a fascination of travel back in the day, and I decided to find out as much as I could about them.

I wasn't disappointed - - - I dug through my books, went to a historic research library, 'surfed the net' (does anyone say that anymore?), and asked docents who work at historic taverns questions, looking for the tiniest bits of information to help me to understand what it was like to travel and stay at a tavern in the colonial times.

This post is the culmination of all of that research.

Our country's founding relied greatly on the tavern.

Cooking on the Hearth

No stoves or fast food restaurants. Everything made from scratch.

What was it like for our colonial ancestors to prepare, cook, and eat their meals, and what kinds of food were available to them? How did they keep their foodstuffs from spoiling and rotting?

If you have questions such as this, I believe you will enjoy this post.

In the Good Old Colony Days

A concise pictorial to everyday life in America's colonies. And I do mean "pictorial," for there are over 80 photos included, covering nearly every aspect of colonial life.

I try to touch on most major topics of the period with links to read more detailed accounts.

This just may be my very favorite of all my postings. If it isn't, it's in the top 2!

It's the Little Things

Another post that touches on a variety of subjects, such as Shadow Portraits, Bourdaloues, Revolutionary Mothers, and a few other interesting historical odds & ends.

A Year on a Colonial Farm

See what it was really like, month to month, for farm folks like Samuel Daggett and others as you spend all four seasons on an 18th century farm.

What many visitors don't realize is that inside these hallowed walls of history (Greenfield Village) there are three specific homesteads which are situated near each other, and the long past inhabitants of each of these historic 18th century houses played a role to some varying degree in the Revolutionary War.

This is their collective story.

This posting is geared toward the reader who has a basic interest in the average daily occurrences of 18th century citizens, and thus, will hopefully help to give an idea of more of what went on inside many colonial homes. Thus, as mentioned, it is not a "how-to" guide, but a "how they did it" informational, for it was a process every man, woman, and child would be quite aware of, even if they didn't necessarily do it themselves.

Researching 18th Century History

Here is a collection of my favorite books in my library that I use, seemingly, on a daily basis, especially when writing in this Passion for the Past blog.

Other people spend their money on sporting events and the like, I buy books.

In the Night Time: Living in the Age of Candles in Colonial Times

Could you survive living in the era before electric lights or even before the 19th century style oil lamps?

Do you know how many candles you would need for a year?

Do you know what it was like to make candles right from scratch, or what it was like to visit your local chandler?

That's what this posting is about!

Buried Treasure: Stories of the Founding Generation

Interesting true tales of everyday folk of the later 18th century, including an interview with a soldier who was actually at Concord on April 19, 1775, the powder horn of James Pike, the true death-defying, battle-scarred story of Samuel Whittemore, runaway slaves & servants, smallpox inoculations, and Nabby Adams experience having breast cancer.

Quite a history lesson here!

To learn more about the beginning of Greenfield Village, please click HERE

To see the Four Seasons at Firestone Farm, click HERE

Could you survive living in the era before electric lights or even before the 19th century style oil lamps?

Do you know how many candles you would need for a year?

Do you know what it was like to make candles right from scratch, or what it was like to visit your local chandler?

That's what this posting is about!

Interesting true tales of everyday folk of the later 18th century, including an interview with a soldier who was actually at Concord on April 19, 1775, the powder horn of James Pike, the true death-defying, battle-scarred story of Samuel Whittemore, runaway slaves & servants, smallpox inoculations, and Nabby Adams experience having breast cancer.

Quite a history lesson here!

To learn more about the beginning of Greenfield Village, please click HERE

To see the Four Seasons at Firestone Farm, click HERE

~ ~ ~