~A personal account of being immersed in the 18th century at the Waterloo Cabin, with no outside public and no modernisms to bring one back to the present. For what we as living historians accomplished here one simply cannot help but feel to be a part of the past in ways other forms of reenacting cannot replicate~

~ ~ ~

Experiencing the past.

That's what I'm about.

It's not enough for me to "visit" those days of old---I want to feel what they felt in a very real sense.

Even in the cold, cold winter.

These experiences do not happen nearly as often as one would think. However, if you find the right people and the right setting - if you did your historical research and have somewhat of a grasp of the time being portrayed - something wonderful can happen...

~ ~ ~

As I wrote the text of this posting, I asked for recollections from others who participated in this excursion for additional views, and so interspersed throughout you will find some very interesting and thought-provoking perspectives from Charlotte and Rebecca.

In fact, Rebecca entitled hers:

The Sound of Winter Memory,

or a Day Given to Provision

- Rebecca Getchell

"On a frost crisped sunny January day, four reenactors find themselves huddling in a reconstruction of a Colonial log cabin. In wintertime in 1771, we found that the cold in the cabin was colder on the inside than out, and against practical logic we opened the house and let the hearth gradually heat outwards. The hearth became a bustle of feminine energy, and the planned stores of peas were dipped into for a thick Pease soup that would give warmth, sustenance, and last in this cold well past 9 days."

|

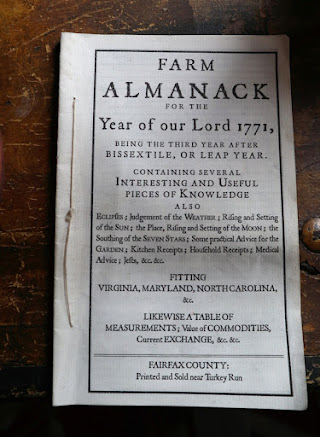

| I am prepared for the growing season with the latest 1771 Farm Almanack. To order this Almanack and other period booklets, please click 18th Century Bibles |

Living history, in so many cases, seems to be put on hold during the months from November through March. A few of us, however, buck the system every-so-often. We're kinda like rebels, you might say. If you recall, a few of us who practice this form of the hobby spent an autumn day in 1770 last October, and it felt like a true time-travel experience. Well, as close as one could get (see the link at the bottom of this post).

Living history.

You see, this facet of our hobby is about keeping the many aspects...the character and lifeblood...of the past alive. So we were very recently at it again, though this time we spent a winter's day in 1771.

I know, I know: baby, it's cold outside!

It certainly was!

And that's the point. You know how I like to experience sort of first-hand what our ancestors felt, and so I came up with the idea of spending a winter's day in and around the frontier log cabin, living as if it were the 18th century. And a few of my friends were very excited to take part.

So why did I choose the year 1771?

To comply with the Farm Almanack I have acquired (see the picture to the left), an implied accessory to help recreate farm life before the Revolutionary War with hints of the upcoming storm on the horizon.

Here in 2021 we are living in a historically unhinged period, with the covid, the politics...yeah...you know...

So why leave one precarious time to visit another?

Because we did not choose to go back to a frontier cabin on January 23, 1771; we were sent...we had no choice. The four of us just happened to find ourselves --zap! -- there -- on a time-travel journey where we, out of necessity, had to utilize and hone the colonist's skills as our own.

|

| Your hosts for the day~ |

Oh! The powers in this strange universe...giving us this grand opportunity to experience a small snippet of what our ancestor's lives were like during an 18th century winter's day.

With the pictures that were taken (each of us *snuck* a mostly stealth camera of some sort back in time with us), and with the text included, it is my hope that a picture of the past can be painted, as well as recorded - a sort of journal you might say - of our time back there. Though we are 21st century folk, I like to think we accomplished our goal in having a pretty fair idea of how life looked in 1771. We were not perfect, mind you. But we certainly were headed in the right direction.

I hope you enjoy the journey...

Ah...here we are---our home on the Pennsylvania frontier, 1771!

Why, just how did we get here?

Wonders never cease...

|

The cabin on the right is used for storage, while the one on the left is... ...our little cabin home. |

"This day Jack Frost bites very hard..." says a 1772 diary entry.

I could have written that note, for my toes in the leather buckle shoes I wore felt the stinging bite of Jack Frost from almost as soon as I arrived, and especially after being in the cold and snow - they had not ached like this in a long time - and because the inside of the cabin wasn't really much warmer than the outside, it took a while for the "thaw" to take place.

They did, however, somewhat come back to life when I defrosted them while standing at the fireplace.

|

| The homespun yarn mitts Larissa wore inside and out. |

In the attempt to cope with cold, winter could be anything from inconvenient to challenging to deadly for most American colonists. We, just like the forebears we were emulating, put up with the inconvenience and took up the challenge of keeping warm and busy in a colonial winter.

Anne Eliza Clark thanked her mother for the yarn mitts, which were of “great service to me when I sweep my chamber and make my bed.” Mittens were commonly worn inside as well as outside because, in many cases, there was little difference in the temperature. Much of the heat escaped up chimneys, and drafts were always a problem. Without the aid of room screens and fireplace screens, a person could feel both hot and cold at the same time standing in front of a fire.

The time we are representing here was during what we now call "The Little Ice Age," a period when the world saw much harsher winters - a noticeable lowering of temps in comparison to today with higher amounts of snow.

As horrible as all of this may sound for our colonial ancestors, we must remember that this was the environment in which they lived. Yes, it was still cold, but they survived for they were used to it and could deal with it much better than we imagine they could, similar to those of us in the modern age without air-conditioning who are accustomed to the higher temperatures of summer better than those who have that a/c luxury.

For us at the cabin, our January day was one of the coldest of the 2020/2021 winter season up to that point, with temperatures in the teens and low twenties. That, in a historical sense, pleased us more than if we had a January thaw instead.

We felt the cold.

The frontier farm couple of modest means relied heavily on their family for labor, and what they grew during the growing season depended on their location. But in general, aside from the wheat and corn, as well as a variety of squash and vegetables from their kitchen gardens, farms typically would have nearby orchards of apples and fields of strawberries, blueberries, and raspberries, all of which would have been made into jams, jellies, tarts, pies, fritters, or dried...and all would help sustain the family over the cold months from late fall until spring.

Farmers also grew cotton, hemp, and flax, cobbled their own shoes, and constructed their own furniture; there was never a shortage of work for the eighteenth century family: women's chores included (but were not limited to) laundry, sewing, spinning & dyeing, washing, candle making, preparing & cooking food, and caring for young ones...

The men, too, had their chores to fill their days as well, including (but not limited to) preparing and then farming the fields (manuring, plowing, harrowing, planting), repairing of fences and tools, the cutting, splitting, and hauling of wood, banking the nighttime fires, hunting and fishing, house and outbuilding repairs, animal care, carrying water, and helping with seasonal projects.

|

| Coming up from the creek with two bucketsful of water. |

|

| Imagine having to carry water from the stream on a daily basis. Lucky for me, due to my bad back, I needn't've worried about it! |

The colonial household ran like a well-oiled machine: everyone had their part and place, and one missing link could throw a wrench into the entire operation.

We are no longer an agricultural nation, which is a recent occurrence in the great scheme of things. The cycle of domestic life, which was closely tied to the land and seasons, had little changed from the beginning of time until very recently in the timeline, for it hasn't been that long in comparison that a new world of technology of refrigeration, gas stoves, electric lighting, and home furnaces transformed the old world into one where the times of the seasons mean little.

|

| Larissa and I do historic presentations together, mostly on farm life, but sometimes as Patriots Paul Revere and Sybil Ludington. But it's our farm life presentation that we enjoy most. |

|

| Here is an image of Charlotte and I in the warmth of the sun. As cold as the temps were, the sun shining down felt very welcome. |

18th-century settlers made the appropriate preparations for winter by gathering up the dried meats, fruits, and beans as well as root vegetables that had been stored since the fall harvest. They would then throw all of these ingredients into a pot to make a hearty if not always appetizing stew.

|

| Let the food preparations begin!. |

Here is a diary entry from Mary Cooper, Long Island farm wife, who wrote in 1769: "Sabbath. A fair day but the wind north east still. O, alas, I am more distrest than ever. I have dinner to get and nothing in the house to cook. My company will not go to meeten. Dirty and distresed. I set my self to make some thing out of littel on."

Keeping a family thriving by making "some thing out of littel on" shows that the colonial women who nourished their family with "nothing in the house to cook" were nothing short of culinary geniuses.

|

| Larissa came up with the idea of having pease porridge. As our story goes, it was made from peas we harvested last fall that were dried and stored, with added salted ham and some stored root vegetables including parsnips. |

|

| Vegetables from the cold root cellar. |

|

| My wife, Patty, is not a living historian, though she is a fine historical presenter at reenactments. That being said, she helped us out and added to our meal by preparing homemade bread the night before to be warmed in the hearth. So good! |

What people chose to eat and how they cooked their meals was what they considered to be edible and familiar. Colonists cooked many dishes from memory and experience, eventually acquiring an 'American character,' and they certainly encountered new foods which, in some cases, came from the local Indians.

|

| Larissa... |

|

| Charlotte |

|

| Rebecca... |

|

| The ladies worked well together preparing our meal; as was done last fall, this cabin experience and experiment had brought the past to life in ways unexpected. |

|

In days of old, the fireplace had always been the one area in the home where all the activity would take place, and it was the same in colonial times; life tended to center around the hearth, for that's where most women of the house (and even some men) seemed to spend a good part of their day, preparing the family meals. And, oh! the familiar smells! |

In my historic culinary research, one of the things that has noticeably changed in recent times is how much actual time is spent making meals today by modern cooks (no, this is not a male-female thing. I am speaking in generality here). With "innovations" such as microwaves, frozen "tv" dinners, pre-packaged foods, and fast food restaurants, the time and energy spent doing this oh-so-important job of food preparation is nowhere near what our ancestors did.

Pride in cooking seems to have gone out the window as well.

| ||

| As an orange-red flame burned on the hearth, streaks of sunlight gleamed through the east windows...the sun warming the floor, thus warming the room...a little... Yes, we left the east door open as well, for the sun did help to bring the temperature inside up slightly.

|

Many of the furnishings and tools you see we brought to the cabin ourselves. A few of us collect replicated 18th century items for use either in our own homes or at events such as this.

At the bottom of this post will be a link to what I have in my 18th century collectables.

Sometimes we need a moment or two to take it all in...so Charlotte grabbed a few spare minutes to herself...

|

| "While sitting on the tree stump I was just taking in the warmth of the sun and the sound of the birds. I couldn’t hear any motors or traffic or anything like that...it was just serene. I said a prayer of thanks for the beauty all around us."  |

|

| Rebecca took time out to read from the Farm Almanack - the one from 1771 shown at the top of this posting. There is much that can be learned about everyday life by reading the old almanacks and journals. |

|

| By the way, just as was in the 1700s, the "necessary" was outside, a distance from the cabin - distant enough to hinder any odors when the weather is warm. But here in winter, the trek seemed to take forever! Rebecca captured this moment as I was leaving for the...um, great outdoors. |

|

| I found this to be an interesting photo: the sun's rays mixing with a bit of the smoke from the fireplace...the wind a-blowing down the chimney, smoke finding its way into the cabin |

The deep fireplaces of most homes, which permitted indoor cooking, also let a significant amount of smoke into the home. The failure of chimneys to carry smoke out of the dwelling remained problematic through the eighteenth century. Until a better understanding of the true nature of heat became widespread, chimneys lacked designs capable of effectively heating as well as drawing smoke out of the home. It wasn't until the 1740s that Benjamin Franklin invented the “Pennsylvanian Fire Place” to improve the efficiency of heating homes. Franklin also published the pamphlet “Observations on the Causes and Cure of Smoky Chimneys” in 1787.

|

Cooking on the hearth - the center of the colonial home - has been thoroughly romanticized, and yet it remains an art that few today have experienced. |

|

| Larissa adds water to the porridge. |

As mentioned earlier, Larissa and Rebecca are long-time Greenfield Village employees and are well-versed in 18th century domestic life. However, Charlotte, in the picture below, is another Greenfield Village employee---or, rather, former employee, for she recently retired from there, though her job was as a worker inside the 1850s Eagle Tavern, one of my favorite historical dining experiences. She, too, earned quite a bit of hearth cooking experience during our cabin excursions.

A learning experience for all.

|

| Charlotte fried up the bacon. |

I've spent countless hours inside the 1760s Daggett House watching Larissa and Rebecca (and other presenters) cook on the hearth, wishing and hoping that one day I could somehow possibly spend an entire day there, taking part in the historical activities with them and the other presenters, and perhaps even join them in feasting upon the 18th century meal. Well, I knew it would be impossible for something like that to happen for me at Greenfield Village, for I am not an employee there.

But I did get "the Daggett experience" here...and more:

As the man of the house, it was I who gave thanks to our Lord for all of His blessings upon us:

|

| Okay---so I look dorky as I pray - God still appreciated it! But I posted this shot to show the delicious food the girls worked on most of the day. It was so good! |

So, for our dinner on this cold January day, we had pease porridge.

Porridge is, by etymology definition, a "thickened soup of vegetables boiled in water, with or without meat," and is also an alteration of the Middle English "pottage."

As Charlotte mentioned, "I loved how we began the day with a recitation of 'Pease Porridge Hot' in a round." Yes, each one of us took a line as we stood in a circle.

The earliest recorded version of "Pease Porridge Hot" was written as a riddle found in John Newbery's Mother Goose's Melody (from 1760):

Pease Porridge hot,

Pease Porridge cold,

Pease Porridge in the Pot

Nine Days old,

Spell me that in four letters;

I will: T H A T -

|

| The pease porridge was so thick you could eat it with a knife. And we also had bread, cabbage with bacon, onion, and smoked sausage, as well as sweet potato pan bread. Cheese and pickles, too. A savory meal indeed. Note the two-prong fork, eating knife, and horn spoon. |

One of the interesting features of our dinner was the use of the various 18th century dinnerware we had, including eating knives and horn spoons. Prior to the American Revolution, most Americans ate with spoons made from shell, horn, wood or gourds. The blunt-tipped knives imported to the colonies were the precursors to the fork and often food was brought to the mouth on the flat edge of the knife. Until the later 18th century, forks, usually two-pronged, were still uncommon in the colonies and in some cases deemed a curiosity; their job was to hold onto the food item on the plate while cutting it into smaller pieces. It was the spoon and knife that was the most common way to bring the food to your mouth. Since the new blunt knives made it difficult to spear food, the two-prong fork was used in its stead — yet still not so helpful for holding bites of food.

We did use the utensils in the traditional manner of our colonial counterparts: the horn spoon, the eating knife, the two-pronged fork for holding the meat. I like that we had all of what we needed for our mealtime to also be historically correct.

|

| Charlotte told us that she "went into the root cellar last night to gather some cabbage, carrots, and onion. Brought in some sausage and bacon from the smoke house. I’m going to fry some sweet potato flat bread at the cabin too." And she certainly did! |

There also could be wooden bowls, trenchers, and plates among the other types.

But it was not only wood tableware that folks ate from. Stoneware was popular and would have been seen in middle and lowering classes. Redware was popular, especially with the middling class, depending on the location for access to the iron-stained red clay.

Though not brought for this event, pewter was also fashionable amongst colonists. However it was more expensive than stoneware or redware. Initially pewter was for the upper class, but by the time of the American Revolution it was seen on many merchant-class table-boards.

Tankards for drinking were made of all three materials listed here: wood, redware, and pewter. Oh, and leather also.

|

After dinner I read aloud from the Almanack and then we simply sat back and enjoyed pleasant conversation, speaking mainly of how those who actually lived in the colonial period survived in such frigid weather. But it was not long before we found the coldness seeping into our bones once again. Time to get moving to get the blood circulating. |

|

| Contemplating my next chore - hopefully one that will keep me warm~ "Although winter was not the season for hard fieldwork, it was a time when processing of harvests and spinning and weaving of textiles could more easily be accomplished for the upcoming year. Although the days were shortened by the available light, the sounds and memories of winter in the house guided hands even in darkening rooms." - Rebecca The textile arts: preparing flax for spinning...that's up next! |

Wool preparation for spinning is more commonly shown today at historic reenactments, and more often than not, that's what we usually will see in the museums as well. So I thought I would present a quick - very quick - lesson on flax:

The flax-production began in the spring, as Matthew Patton, a New Hampshire farmer, did on May 18, 1787, when he reported in his diary: "I sowed about 1 of a bushel of flax seed and I suppose near as many pease." The very same day, 150 miles away in Hallowell, Maine, Martha Ballard's husband was engaged in similar work: "Clear...Mr. Ballard ploughed flax in," she wrote. Since the seed was light, it took skill to distribute it evenly and well.

"I wed (weed) flax," Ballard wrote on June 16, 1788, a month after her husband completed sowing. Her patch of flax was an extension of her garden. Patton's crop was larger. With three quarters of a bushel he could have seeded half an acre.

Just before it matures, it is pulled from the ground, roots and all. The harvest for these folk began the last week of July or the first week of August and lasted three or four days. "Finished pooling flax," Matthew Patton wrote. Martha Ballard and her daughters usually did their own pulling, lifting the plants carefully by the roots, holding the stems as straight as possible to avoid tangling, then stacking them in neat bundles for later processing. Sometimes they were spreading cloth made from last year's crop on the grass to bleach while they were harvesting the new one. Growing flax and turning it into linen for clothes requires growing a variety suitable for fiber to spin.

"I wed (weed) flax," Ballard wrote on June 16, 1788, a month after her husband completed sowing. Her patch of flax was an extension of her garden. Patton's crop was larger. With three quarters of a bushel he could have seeded half an acre.

Just before it matures, it is pulled from the ground, roots and all. The harvest for these folk began the last week of July or the first week of August and lasted three or four days. "Finished pooling flax," Matthew Patton wrote. Martha Ballard and her daughters usually did their own pulling, lifting the plants carefully by the roots, holding the stems as straight as possible to avoid tangling, then stacking them in neat bundles for later processing. Sometimes they were spreading cloth made from last year's crop on the grass to bleach while they were harvesting the new one. Growing flax and turning it into linen for clothes requires growing a variety suitable for fiber to spin.

Once picked, the plant is submerged in water in order to rot the useless part. This is called retting, considered one of the most important stages in the flax process. The flax is then spread on the grass (called dew retting) to dry.

|

| In the crate we see flax, already retted and ready for the process before spinning can begin. After the three steps of flax preparation is completed, roughly 10 to 20 percent of the plant will be useful as fiber for spinning while the other 80 to 90 percent is unspin-able chaff. |

Pulling the flax from the crate, the next step occurs, which is using the flax break:

| ||

A flax break is a tool with wooden blades on top and bottom. The top blades are hinged at one end and can be raised and lowered to smash the stalks. A large bundle is centered at the hinge (or wider) end of the break; the upper meshes with the lower and comes down with a bang upon the flax which is struck as it gradually moves to the smaller end, softening the brittle stalks as well as removing the useless parts.

|

Let's move on to the next step: scutching.

|

| After using the flax break, the remains are then scutched to remove more broken shives from the tough line fiber. Scutching is a scraping process where the broken flax is laid over the top edge of the upright board and a wooden knife is used to scrape off the chaff from the line fiber. |

|

| My wife, God Bless her, surprised me with a scutching board & knife this past Christmas! Unbeknownst to me, she had our friend, Tony, make it, and did so from the pictures sent to him of the board inside the 1760s Daggett House. What an awesome gift and a wonderful surprise! This was my first time using it - almost a month after Christmas. |

|

| After the flax break and scutching board, it was time to use the hackle (also known as a heshle or hatchel). |

"I am heshling flax."

Molly Cooper November 15, 1769

"I have hatcheled 14 pounds flax from the swingle."

Martha Ballard March 16, 1795

"I have been carding tow."

Martha Ballard March 24, 1797

|

| The hackle is one scary looking but important tool, for it is the last of the three steps in preparing/softening the flax fibers to be spun. |

|

| The flax is pulled through the hackling spikes (also referred to as combs), which parts the locked fibers, splits and straightens them, cleans them, removes the fibrous core and impurities, all to prepare them for spinning. |

The short, tangled fibers left in the combs of the hackle, which are useless for spinning, are called "tow" flax and were used for stuffing mattresses, cleaning rifle barrels of black powder residue, as a scrub pad for cleaning cast iron utensils, as fire starter (tinder) for flint & steel (flax fibers are quite flammable in their unspun state and can catch a spark easily), and even to be made into rope.

As for the softened flax, its use was for spinning:

|

| Due to the patriotic fervor of women in the later 1760s and into the 1770s, spinning - "homespun" - became extremely popular throughout the 13 colonies. |

Women in the American Colonies played a critical role in boycotting the importation of British goods

in protest of increased taxation on everyday items. Although Parliament repealed the Stamp Act, they replaced it with the odious Townsend Duties. Suddenly clergymen, militia captains, printers, politicians, and urban gentlewomen who had never before touched a spinning wheel took a new interest in household production. “Women determined the Condition of Men, by means of their spinning wheels.”

Between March 1768 and October 1770, New England newspapers reported more than sixty spinning meetings held all along the coast from Maine to Long Island. Soon there were reports of large gatherings all along the coat of Massachusetts and into Rhode Island.

Out on the frontier, however, spinning was a necessity.

|

| Rebecca tied the prepared flax onto the distaff using ribbon. |

|

| Larissa and Rebecca working at the wheel |

|

| Larissa and Rebecca working at the wheel |

|

| Flax spinning wheels are generally smaller in diameter. The smaller the diameter the faster the wheel turns, and flax can take a hard twist to make a strong thread. |

|

| Once the flax fibers are spun into a line of thread, it is called linen at that point. |

|

| Because the flax fibers are jointed, like bamboo, it is the interlocking of the joints during spinning that prevents the thread from unraveling and makes flax such a perfect spinning fiber. |

|

| From raw flax to linen thread. Since I first posted these photos publicly on Facebook and MeWe, I've had two period book binders contact me about using the linen thread to bind their books. |

This was my first time actually going through the entire process, from "raw" flax through linen thread, and it made me feel so good knowing that though both have spun linen, this was Rebecca and Larissa's first time taking part and witnessing the complete process as well, for the flax they spin at Daggett comes to them already processed.

~Sounds: Hearing History as our Ancestors Heard It.~

|

| These are the shadows of things that have been... |

What I did not hear was a radio/music playing or voices coming from a TV as background noise or the tapping on a computer keyboard or smart phone bleeps. No cars or trucks or booming bass speakers.

Rebecca noted the sounds of the past as well, and I enjoyed her perspective:

"The clicking of knitting needles, clipping of flax breaks, scraping of scrutching knives on their boards, flicking of hanks of flax being combed by the hackle, the whirring of the flax wheel, rhythmic walking of processing of any wool that was left from last Spring's shearing on the high wheel, the beat of the battening of the weft on the loom of the itinerant weaver, and the slipping of the needle through mending, and made clothes and linens, these were the sounds of winter industry."

Perfectly put, Rebecca.

Just the sounds of the past...most of which we heard.

The late afternoon was nigh, and thoughts of the day commenced. Charlotte said, "I was so thankful for a little snow and a warm sun. As the day warmed and then the temps dropped by afternoon I was struck with the reality of always being cold and planning your every task to deal with the cold. My inner core just tenses up in the cold. Just imagine how mentally and physically wearing the long winter was on our frontier ancestors. We are such whimps!! Without constant preparing for winter your life and those of your family could be severely compromised."

|

And you know the sun's setting fast, and just like they say nothing good ever lasts... But that's not necessarily true; the day was wonderful, and the memories made will last for a long time to come. |

As the sun set, it was actually darker inside the cabin than what the following photographs depict. A couple pictures show this well while others made it look a bit brighter than actuality.

I wish the true look could have come out in all the images:

|

| So...evening had come to pass...and we see Larissa & Charlotte at the hearth~ If you look to the left you can see the lit lanthorn of which the translucent was made of cow's horn - very period correct for the time. |

|

| Rebecca and Charlotte enjoyed the bit of warmth emanating from the hearth. |

|

| Rebecca and I also made the attempt to gather some warmth from the fire. We are very happy to have her become a part of Citizens of the American Colonies, for the fact that she is well acquainted with the colonial past and the chores & duties of a young lady of the period is such a bonus. History is in her soul.. |

As we sat and conversed, we came to realize just how close we were to living out the ancient diary entries we've read. As experienced we are to living history, this experience truly was, for us, living history.

|

When the sun goes down, and the clouds all frown... The four of us had a wonderful day learning about the past through experience. I am so very proud and happy of the members of Citizens of the American Colonies for taking on such an endeavor. There will be more to come. |

Some people call what we do "pretending."

I am here to say this is not pretending. As historians we make the attempt to live history and bring to life what we read from journals, diaries, letters, and even broadsides/newspapers. In doing so we can pass these experiences on as teaching moments we have during our events and presentations. It also satisfies the hunger and thirst we have - this passion we have for the past. It may be sorely overlooked in history books at schools and colleges, but history is made from regular everyday people - the citizens - who survived under what we would consider harsh conditions. We need to learn of those who are not unlike you and I - the majority - who may not have gotten their names in the history books, but were, nonetheless, every bit as great and important as anyone else - (like you and I). Unfortunately, many folks have a tendency in our day and age to over-simplify the roles of a colonial family with the insinuation that those who lived before our own "enlightened" time were backwoods, backwards, and just not as intelligent as we are. But I heard such a great line from someone on C-Span a few years back that explains it all perfectly: "People in the past were every bit as smart as people are today. They just lived in a different time."

That's how we can, as historians, fully understand the times in which they lived.

And perhaps not be so judgmental in looking back at them from the 21st century.

They do not deserve such harsh judgment.

So for our latest historical experience, this winter day spent in 1771 was biting cold with the temperature in the teens and twenties. A few inches of snow covered the ground, with icy spots here and there. A frigid wind blew in from the north. It was perfect for what we wanted to experience, however way we could, in a similar vein our colonial forbearers did, even if only for a day. We were living the time rather than presenting the time.

And we did.

But then the magic ended...and we returned to 2021.

Just like that.

This was as close to time-travel as one can get....

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

I cannot thank the good folks at the Waterloo Farm Museum enough for allowing us to live out long-time historical dreams. I appreciate the trust you have given us.

See you in the spring!

Also, so many thanks to the wonderful living historians who joined me - Larissa, Charlotte, and Rebecca - for it was because of their want of these time-travel experiences that we could, together, make it happen.

I am proud to call you my friends.

And it's to them I also give thanks for taking great pictures: between the four of us, our day was captured in the sixty-something images you see in today's posting.

As for a few sources - - - - - -

Flax information taken from the pamphlet The Textile Tools of Colonial Homes By Marion & Walter Channing

Some of the dinnerware information came from THIS site.

Chimney and fireplace information came from HERE.

But wait! There's more - - - - - - - !!!

Ken's Blooper!

So----I was walking backward, attempting to set up a "quick sketch" picture (farb!) and, thinking I was in the clear of the stump from the tree we felled last fall, I fell backwards right on top of it---hard! So hard, in fact, that I literally bounced off the stump and slammed flat on my back onto the cold, hard, snow-covered ground.

|

| Oh, it's hard to go down easy (as Dan Fogelberg once sang)...and I had to laugh alongside everyone else. I mean, what could I do? According to Larissa, my feet went above my head! I felt like a dork! |

|

| But I got up, with a little help from my friend, and, all covered in snow, carried on with the day's activities. |

|

| Anyhow, yeah, the next day my tailbone hurt pretty good, and the pain my back, with my sciatic problem, let me know it was not happy with me, and I was walking like a decrepit 90 year old man for a day or two. But I got over it, and within a few days I was almost back to my "normal" self...except for my tailbone - - three weeks out and it still hurts. Yeah, I hit pretty hard. |

Until next time, see you in time.

To read about our autumn in 1770, please click HERE.

To read a bit about my reproduction18th century collectables, click HERE.To read about winter in colonial times, please click HERE.

~ ~ ~

Just like last October, we had a fire in the hearth for not only a hearty meal,

Just like last October, we had a fire in the hearth for not only a hearty meal,

9 comments:

I hope you will someday gather all your blog posts and place them in book form! All of your post was so interesting; I can't pick a favorite part, but being reminded of how difficult it was to prepare food really struck a chord with me. Our ancestors were made of tougher stuff than is commonly thought. I also liked seeing your flax break and now your new scutching tools in use.

Another fascinating venture into the past!

Thank you both so much. This really means a lot to me.

I went back in time with you, enjoying all the photos, and your comments. Thanks so much for posting. I will be posting tomorrow about my ancestors who traveled west into KY and then MO, and ended up in Texas...and I mention how amazing it must have been to prepare food for the family when on the trail! And then the huge endeavor of starting a new home in a new place. It's amazing!

It honestly boggles the mind, doesn't it. My respect for those who came before continues to grow.

I too love all of this. There is a small scythe to the left of the mantle- what was it used for? (I have 1 slightly larger because I thought it was "cool"). I also have a small 2 prong fork - and a larger 3 prong one I thought was for the garden, but after reading this, it might have been for meats. ??? Also, there is a utensil between the 2 large forks hanging above the fire. Is it a spatula or a scraper or?

Oh, the sounds of the past. You are so right. The sounds marked the hours, the days and the seasons. I've grown increasingly fond of the quiet sounds of the working home. Thank you for posting. I'm so glad to have found your blog.

Most of what you see hanging at the fireplace was already there when we arrived.

The forks would have been used partly for checking and/or flipping the meat (any garden tools would not have been hanging with cooking utensils).

Yes, that spatula-type instrument was used by the ladies as a spatula.

I think the link here might help you:

https://www.millhamhardware.com/cooking-utensils.htm

Thank you! What a great site!

Great fun and a cheery chuckle to the fall. I loved this post too ❤

Post a Comment